The still life is a genre of art adopted by photographers from the earliest days of the medium. Photographers found inspiration in the still life paintings of the early 17th century. (1) A still life motif is used for a variety of reasons, including purposeful investigation, and experimentation of technique and expression. This Commentary on Still Life images is Part 1 of a four part series about artists met during this year’s Fotofest. These artists are taking photography in directions that are challenging, compelling and creating a “new vision”. The work of Robert Langham III, a Tyler, Texas based photographer, creates still life images. In his two series “Blackfork Bestiary” and “Magic & Logic”, he incorporates animals, objects and staging as an historical exploration of where he lives. (2)

What is a still life? “The term still life in English is derived from the Dutch stilleven. … Most dictionaries define still life as a picture consisting predominantly of inanimate objects such as fruit, flowers, dead game, and vessels… ”. (3) Others have referred to a “still life” from the French words, “nature morte”, in a literal sense, dead nature. (4) Another definition is: “A still life is a picture of objects that have been arranged in a composition. Photographic still lifes are usually made in a studio setting where artists use precise composition and lighting to render shape, show the surface of objects, establish mood, and draw the viewer’s attention to certain elements. Artists often use natural and manmade objects carefully selected and placed in the scene to serve as symbols or metaphors.” (5) Over time, what is a “still life” has become even more broadly viewed. The objects used do not have to be inanimate nor dead. The image could be something we might not consider a traditional still life image such as a secondhand shop window (Walker Evans) or a stack of books (Manuel Alvarez Bravo). (6)

Still life images were an important chapter in photography’s challenge to be respected as an art form. (7) “WHF [William Henry Fox] Talbot’s Insect Wings, as seen in a Solar Microscope (c.1840), which [ is one of ] the earliest photographs, sits comfortably alongside modern interpretations of the still life genre”. (8) Two of Roger Fenton’s albumen silver print images of “Decanter and Fruit” and “Tankard and Fruit” (both done in 1860), are absolutely exceptional and beautiful images, even when examined more than 150 years later. (9) There is a very long list of other photographers who engaged with still life images such as Paul Outerbridge, Andre Kertesz, Paul Strand, Edward Weston, Man Ray; who created a remarkable image,“Dead Leaf”, Irving Penn, and the exploding vases of Ori Gersht in his series “Blow up”. (10) There are also more contemporary, yet widely different, still life works of Vadim Gushchin (11), Paulette Tavormina (12) or collaged images of Torrie Groening (13).

Langham’s series “Blackfork Beastiary” and “Magic and Logic” are not formless and accidental, but carefully crafted, set and purposeful. As Szarkowski wrote in “The Photographer’s Eye”, “…the image would survive the subject and become the remembered reality”. (14) Langham takes the raw information from nature and inserts other objects that create a narrative. His images are not documentary. Each image has its own staging in which a visual story is performed.

His subjects in “Blackfork Beastiary” are live animals found near his home in Tyler, Texas. He studied the area around Tyler and the “Blackfork” watershed for which the series is named. Langham was fascinated with both the origins of man into the area, and their coexistence with the land, animals and their habitat. He photographs these creatures in both natural and man-made settings, when the situation hits him as appropriate, and then releases the animals back into their natural environment. Friends and neighbors, knowing his interest in creatures in the area, insects, reptiles, amphibians , wild and domestic, bring him their finds.

The snake in the martini glass certainly captures attention. The small copperhead, a poisonous snake by the way, was found close by (and later placed near where it was found, back into nature, outside). Langham waited patiently for the snake to make the right move to capture that flick of the tongue. An image very reminiscent of another famous photograph by Richard Avedon, “Nastassja Kinski and the Serpent “(1981). In this photograph, Avedon caught that critical lick of the snake’s tongue that makes the image ever more special, and seeming indifferent cool of Kinski. Using the martini glass may have been brilliant as its shape allowed the snake to take such an interesting pose, unlike a hat or a box.

Early in his career he started with landscape photography. With landscapes, he felt he was capturing what nature controlled and created, but not something he managed. With still life photography, he controls (almost) everything in the image: the light, the setting, the arrangement. None of the creatures show movement, so Langham took the image at a fast enough shutter speed to capture just the moment of time rather than a span of time, which would occur in earlier still life images. The camera, film and paper of the early still life images would not have been able to do this. In the 1800’s, motion would have been detected on the less light sensitive film used. Most likely, while photography then imitated painting, the use of “nature morte” enabled a more precise image avoiding motion blur from live subjects.

The image, “Cicada Hand” would bring chills to the uninformed about this harmless, but noisy, periodical insect. Hands appear through out photography, with no more famous a pair than those of Georgia O’Keefe repeatedly photographed by Alfred Steiglitz. This hand image, however, brings to mind a return to childhood. It conveys a sense of the innocence and exploration we enjoyed as children, uninhibited by the baggage of knowledge we gathered as we aged. The image has the same joy of exploration that is felt in the image “Fireflies” (1992) by Keith Carter, another well-known East Texas artist and photographer. Langham’s image is a study in the different emotions triggered within us. In this case, this may be “seeing” the sound of the cicada,” the feel of its legs on the skin, and sensing the stillness with which the hand is held so the bugs don’t fly away and all the while the joy of discovering one of nature’s wonders that emerges every 13 to 17 years from the ground by the millions.

The images seem to have a relatively consistent vantage point, only the subjects change. There is boldness to the images despite a “dead-pan” presentation that reminds one of the Bernd & Hilla Becker’s Dusseldorf School style of photographing water towers and other structures. Unlike his landscape work where there are changes in elevation, distanced position, each of the still life images show a somewhat consistent focus on the subject and props as if we are seated in a theater looking at a stage with changing scenes for each performance. Langham commented that with landscapes, “mother nature” controls the reality of the moment. In these images , in his studio, he is showing us that he controls the reality of the moment.

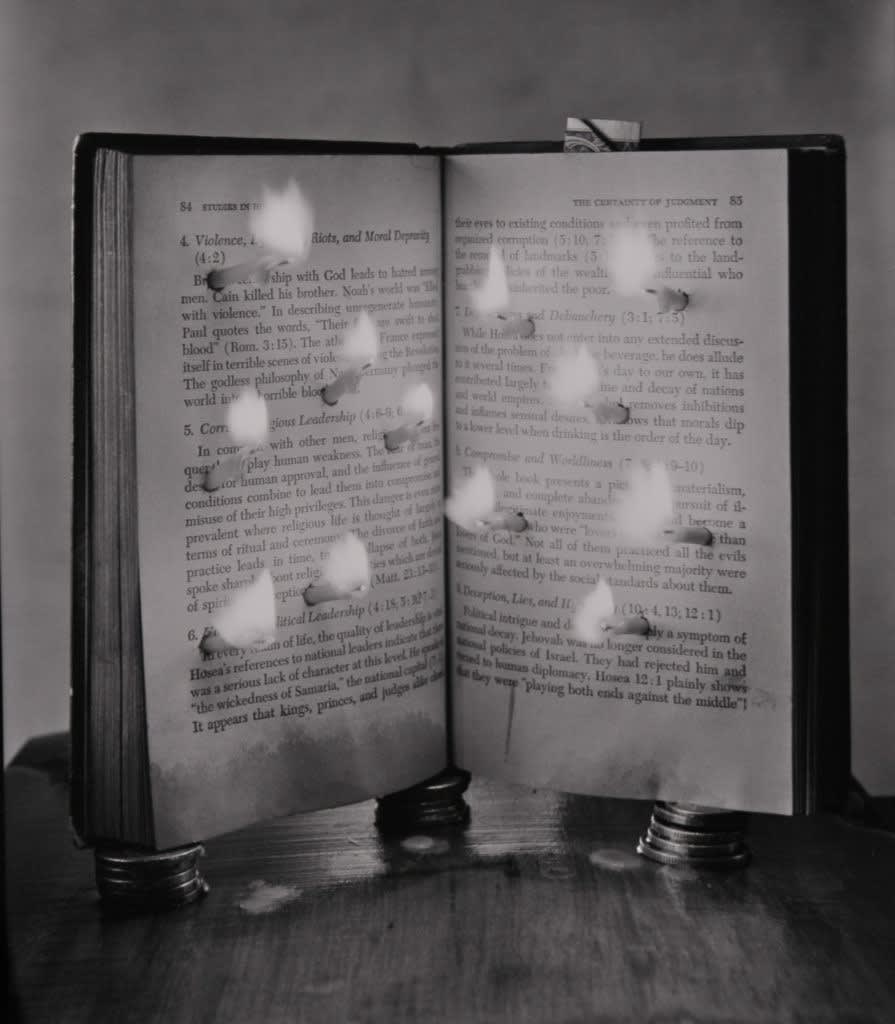

“Illuminated Manuscript” in a very different still life, and almost a performance piece, as many of Langham’s works might be alternatively described. We can read the title of the book or chapter as “The Certainty of Judgment”. On the pages, illuminated by the burning candles, we can see subsections describing violence, corruption, drunkenness, debauchery, compromise and worldliness, deceptions and lies. We sense that the text is an instructional religious text. Langham, as the artist, had a choice to make of what book, what chapter and what pages would be used for this image. He could have chosen a book ranging from a children’s book to a text on physics. He could have chosen from any number of topics this text covers, but he chose one containing the words listed above. The burning candles impaled into the pages of the book can take on several possible meanings. Are the candles merely representative of additional light to read the text, direct our attention, instruct us on the urgency of the messages contained as the candles burn out and either extinguish themselves or set the entire book on fire? Is Langham suggesting the viewer have an interest and belief in the text, or is he suggesting a disbelief in the words and views expressed by implying the book should be burned? The book is set up, off the table. Is this to imply a certain reverence, faith or belief for the messages in the text, or imply a baselessness in the text that is unanchored or grounded firmly in logic? I suspect the former in both cases, rather than the later, but the wonder of the image is allowing the viewer to engage, think and be challenged to come to their own viewpoint.

His still life series involve what he terms “kinetic still life”. As Langham wrote in his own statement on the series “Magic & Logic”: “This work explores burning, melting, blooming, wilting, balancing, et. (sic) … some of the images cannot be seen until multiple exposures are complete. … Objects in “Magic & Logic” come from the yard, the storeroom, the garbage, street, flowerbeds and lawns of my neighbors.” He starts his process of image creation “just guessing”, as he is fond of saying. Langham does not want to be influenced or tainted by knowledge of what other artists have done, in particular photograph with an animal, object or subject. His views are, in his mind, part of his own personal journey that he has set out upon. The path he follows is very anchored to his geographic area and what nature has placed within it.

The process is “kinetic” in the sense that the object or animal is always changing and not static. Therefore, the still life is not reproducible. That moment the image is captured has a “limited life”. His process is a series of mistakes, starting with a seed of an idea that he allows to develop. Maybe, after much experimentation it evolves into a “great idea”. Maybe, but, at least, it’s an image with which he can feel satisfied. For Langham, a good “emotional” idea must be embedded in the work to have created a great “visual” image. “We’re all visual animals, but to be a visual artist and to have practiced looking at things with an eye for managing a camera and making a two-dimensional piece of art with it, just kind of changes your whole visual perception.” (15)

In the assemblage of “Folded Frozen Flatware”, the viewer can recall the sense of holding a cold fork, albeit, not one as bent, mangled and disarranged as those in this photograph. The image is unlike still life images of kitchen implements we have seen by Paul Strand in “Bowls and Pears” (1916) , Andre Kertesz’s “Bowl with Sugar Cubes” (1928) or even William Eggleston’s kitchen image “St. Simon’s Island, Georgia” (1978). These and many others are neatly set and arranged. Instead, Langham has chosen to freeze different objects in ice, in this case forks, that affirms that this still life arrangement is indeed temporary as the ice melts and the “sculpture” falls apart. It has elements, as do his other images, of changes in the approach to art carried forward from the “Pictures Generation of the 1960s and 1970s for combining a cultural and performance sense with the capture of a photographic image. (16) This work, unlike the others, emphasizes the importance of the performance, recorded and preserved only for the moment that reinforces his approach as a “kinetic” still life.

In all things, we hopefully bring and possess a sense of balance. In his image “Fall Running Scissors”, we are visually cued into several sensations. Balance, as the scissors should normally not stand on the point of one of its blades, but for the fact that the point of one of the blades has been imbedded into a wood plank. There is the contrast in the strength of the metal of the scissors and the delicacy of the leaves. Another contrast is the presumed sharpness of the blades and the softness of the leaf, seemingly frozen in mid air as if falling to the ground. This brings to mind the children’s game of “Rock, Paper, Scissors” (17). On closer examination we see one of the scissor blades appears broken, rendering the scissors almost useless, yet it’s a third blade attached to the scissors. Each leaf seems unharmed, and in fact, a perfect specimen. Five leafs are safely behind the scissor, yet one is between the scissors blades, seemingly unharmed and presumably because one blade is broken, and perhaps not so positioned as to be at risk from the actual working blades. Langham is not telling us what to think, but is giving us an invitation to think and discuss.

In true East Texas tradition, Langham has become a storyteller through images, using the still life genre to convey a history of place, people and interaction,coexistence and impact on this place referred to as East Texas. He sets the stage but leaves the tale untold. The images all require an attention to detail. A viewer can not quickly look at the image and appreciate it. Each image demands study, as each has an “emotional” as well as “visual content. Each image allows the viewer to write their own ending, and to think about what is seen and what might be meant? Getting to a satisfying image is part of a continuous process of experimentation for Langham. That is why he says images cannot be seen until multiple exposures are made. The setting for the image is processed and reprocessed. He views a still life as an instructional exercise for artists to learn and think about what and how an object (or animal) should be shown. Langham compounds this with the patience and planning that goes hand-in-hand with the use of traditional film, with black & white silver gelatin, platinum and palladium prints. A statement attributed to Ansel Adams is : “You don’t take a photograph, you make it”. Robert Langham has embraced that concept and taken his art one step further.

Notes:

- “Still-life painting as an independent genre or specialty first flourished in the Netherlands during the early 1600s, although German and French painters … were also early participants in the development…” from the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s website’ Heilbronn Timeline of Art History. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/nstl/hd_nstl.htm

- Robert Langham’s original works for which he was first known were landscapes, in particular the Shiprock series. Early in his career he worked for and trained with Ansel Adams .He has been a photographic artist and teacher for over 40 years who has always stayed close to his roots in East Texas. http://www.tylerpaper.com/TP-Arts+Entertainment/197545/robert-langham-the-camera-kind-of-a-time-machine-the-darkroom-an-alchemists-miracle.

- “Still Life in Photography” by Paul Martineau, Asst. Curator of Photography at the J. Paul Getty Museum, Getty Publications.

- Op cit., “Still Life in Photography”, Martineau, page 6.

- Museum of Contemporary Photography (MOCP), Columbia College Chicago. “Framing Ideas: Still Life: The object as Subject, Curriculum Guide”.

http://www.mocp.org/pdf/education/MoCP_Ed-StillLife.pdf - “Op Cit., “Still Life in Photography”, see images on pages 46 (Evans) and 48 (Bravo).

- See essays by Sarah Greenough, Curator for Photography at the National Gallery of Art, and Pam Roberts, an independent researcher, writer and Curator of the Royal Photographic Society in Bath (1982 to 2001) in “All the Mighty World: The Photographs of Roger Fenton, 1852-1860”, authored by Gordon Baldwin, Malcolm Daniel and Sarah Greenough, Yale University Press, 2004.

- ”Art of Arrangement: Photography and the Still Life Tradition”, a 2013 exhibition by Greg Hobson, Curator of Photographs, the National Media Museum. http://www.nationalmediamuseum.org.uk/aboutus/pressoffice/2012/october/artofarrangementphotographyandthestilllifetradition. Note that Martineau at the Getty references an even earlier image by the creator of the first photograph, Nicephore Niepce who died in 1833, “The Set Table”, in his text “Still Life in Photography”.

- Op cit.,“All the Mighty World: The Photographs of Roger Fenton, 1852-1860”, Plates 88 and 89.

- Op Cit, “Still Life in Photography”, where images by these artists from the Getty Collection can be found.

- http://vadimgushchin.ru/en/projects/

- http://www.paulettetavormina.com

- http://www.torriegroening.com/grandscenarios. Torrie also has a new series I saw at Fotofest this year, not yet on her website at the time of writing this Commentary, that is very reminiscent of William Henry Fox Talbot’s “Articles of China” (1844).

- “The Photographer’s Eye”, John Szarkowski, The Museum of Modern Art, New York, 1966.

- http://www.tylerpaper.com/TP-Arts+Entertainment/197545/robert-langham-the-camera-kind-of-a-time-machine-the-darkroom-an-alchemists-miracle

- “The members of the Pictures Generation grew up during a decade when art was radically changing. During the ‘60s, the art world saw the rise of diverse and divergent movements from Pop, to Conceptual art, and finally, to Minimalism. Each had its own agenda and style, but all three movements played a part in diminishing the significance of the boundaries between painting, sculpture, photography, and performance.” Article by Alex Greenberg , “What was the Pictures Generation?” (9/23/14), Artspace Magazine.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rock-paper-scissors