Sky Light is an exhibition of two new related bodies of work, Rayleigh Shadows and A Legacy of Shadows, by photographic artist Brenda Biondo. Her interest in light and the environment sparked a decision to move to Colorado many years ago for clearer skies and open landscapes, and her attraction to atmospheric phenomena continues to be a driving factor in her work. With the Sky Light project, Biondo is changing our gaze from looking up at the sky to looking down at shadows.

Her new work moves us to see the world indirectly. The images use the shadows of plants and other objects in an unconventional context that focus a viewer’s attention on specific aspects of the landscape that are often overlooked. She refers to this as “deconstructing the landscape.” She says: “What I mean by ‘deconstructing the landscape’ is that I want to get away from looking at a specific tree, a specific plant, a specific cloud, in the context of foreground, background, etc. – and, instead, look at various components of the landscape outside of their normal contexts. The meaning of ‘deconstruct’ is to reduce something to its constituent parts in order to reinterpret it. Shadows give us the shape of a branch, but it is not the branch that we see. I think this is also important as a way to avoid the cliché of many types of landscape photography.”

Biondo’s previous work, the three related series Paper Skies, Moving Pictures and Modalities, can be considered “skyscapes” — landscapes that focus only on the sky. In Paper Skies and Moving Pictures, light at various times of day and in different seasons was photographed, printed, manipulated, rephotographed and reassembled to create a new way to appreciate sunrises, sunsets and daylight in a manner unlike any before created by other photographers. By putting the sky into unconventional contexts, the work allowed her to challenge viewers’ perception of color and space.

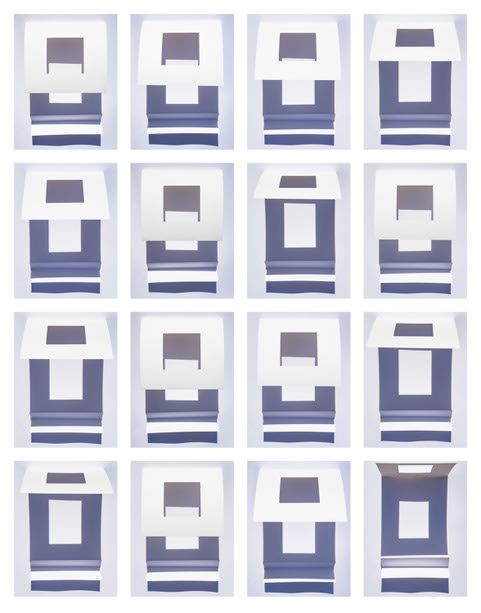

© Brenda Biondo, Grid Variation (wind effect) (2020)

For her new work, from her high-elevation location in the Rocky Mountains, she wondered not only “why is the sky blue?” but also “why are shadows sometimes blue?” Ask yourself, are shadows always black? All is not black, and her images are proof for our disbelieving eyes. The series Rayleigh Shadows examines the physical properties of sunlight and our perception of light, revealing the blueness of shadows in the Colorado mountains. According to Biondo, “‘Rayleigh scattering’ is a scientific term that refers to the blueness of the sky. In sunlight’s visible spectrum, blue wavelengths get scattered by atmospheric molecules more easily than the wavelengths of other colors — which is why the sky appears blue. At high altitudes, this light scattering can be more pronounced. When a shadow is cast outdoors, direct light is blocked, but not ambient light, which is also blue. So casting a shadow onto a white surface under the right conditions results in shadows ranging from blue-grey to purple.”

To create images in the Rayleigh Shadows series, she places rolled, cut and/or folded pieces of white paper on the ground and takes photographs of shadows cast by the paper. The angles of the paper dictate the color and luminosity of the shadows. In a pure sense, the work is only about shadow. It is in A Legacy of Shadows that Biondo takes the next step to integrate the landscape into her images.

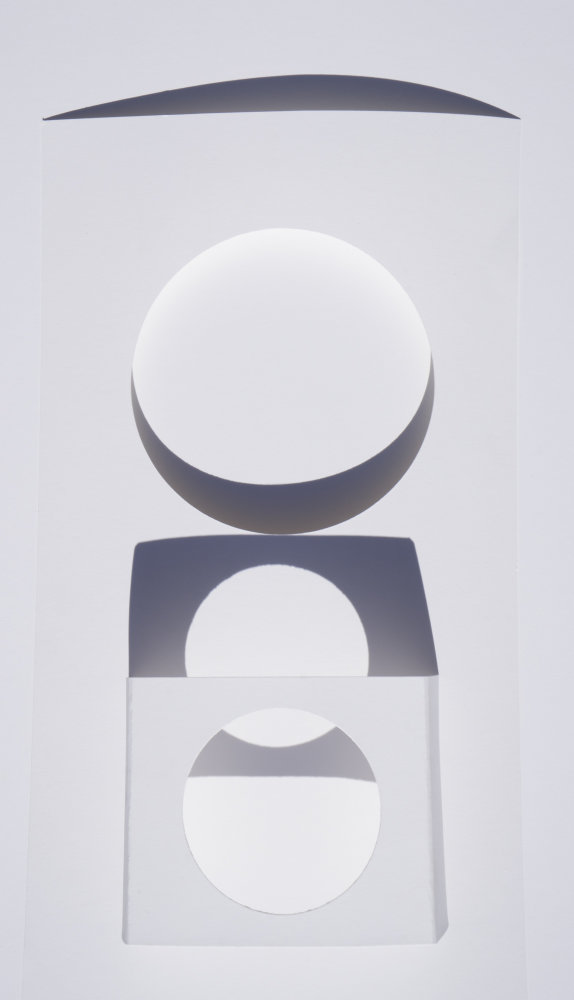

© Brenda Biondo, Rayleigh Shadows no. 6 (2020)

Rayleigh Shadows no. 6 and Grid Variations (Wind Effect) are beautiful examples of Biondo’s unique approach to image creation. She has carried forward her technique of photographing, printing, cutting and bending paper. With Rayleigh Shadows no. 6, white paper is cut, manipulated and positioned to create and capture shadows. The abstraction dominates what we see in a nod to the much earlier works of surrealists. Importantly, none of the image is artificially created in post-production work. As with prior Biondo images, each is a traditional photograph that is captured with one click of the shutter. Grid Variations (Wind Effect) is a grid comprised of 16 panels, each following the same individual technique of Rayleigh Shadows no. 6. With Grid Variations (Wind Effect), Biondo has created an installation that shows the passage of time by capturing images of the paper templates as they are batted about by a light wind during her shoot. Where each could stand on its own within the intent of her project, the repetitive patterns become a challenging installation for light and shadow, and bear evidence of a spontaneous collaboration with environmental conditions.

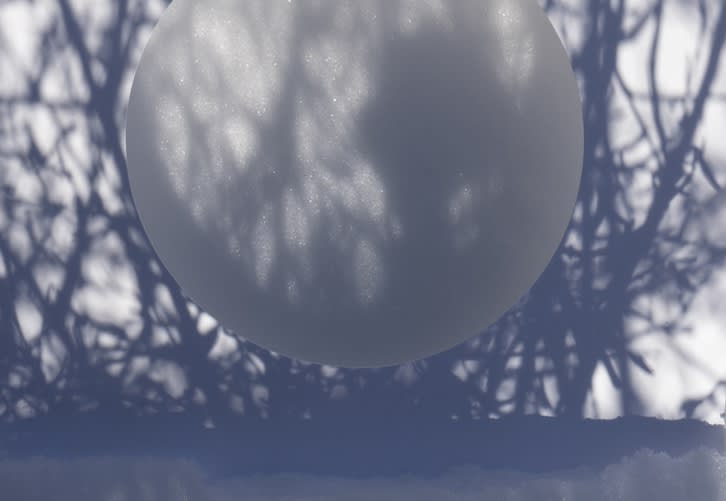

© Brenda Biondo, Shadow Legacy no. 6 (2020)

With A Legacy of Shadows, she captures shadows of plants falling on snow and white paper, imposing shaped fragments of what is seen to reveal parts of nature that are overlooked by our too rapid glance. Within these fragmented shadows, it is not the literal image of the object that is important, but the shadow that forces our imagination to consider what we are seeing.

Biondo plays with these shadows rolling across different surfaces. As light is obstructed, the darkness of shadow is created. She tricks our vision and redirects our perception. The artist is teaching us how to gain pleasure in the simple manipulation of a surface. With a surface that is rounded, the shadows spreads. With a surface is flatter and firmer, the shadow sharpens. The A Legacy of Shadows works are much more about light against physical surfaces or snow following the undulations of ground and rock, rather than just light on paper as was done in Rayleigh Shadows. If one looks closely, we can see that Shadow Legacy no. 5 has shadows flowing over and across folds of paper acting as mounds on a flat surface. In Shadow Legacy no. 18, Biondo uses a circular shape as if looking through a telescope to see the shadows of leaves cast onto flat and rounded surfaces.

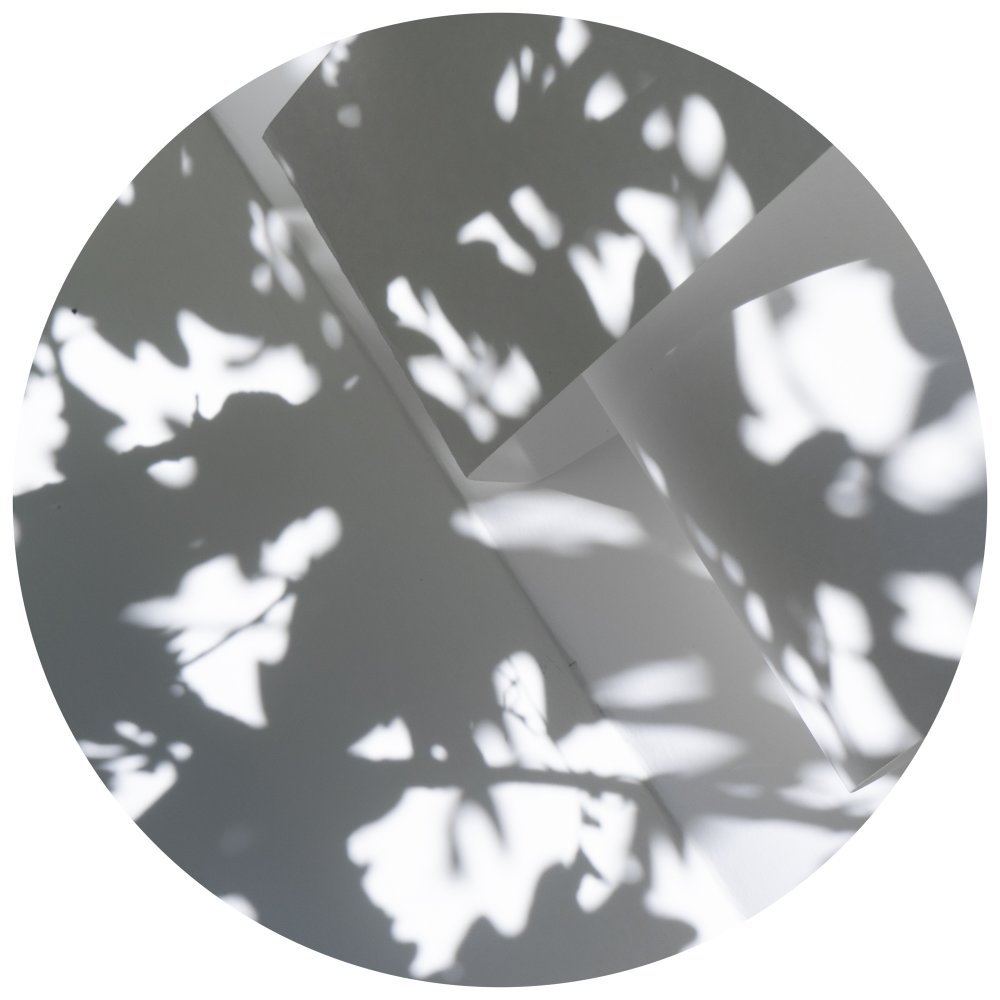

© Brenda Biondo, Shadow Legacy no. 16 (2020)

In one view, we see how shadows sharpen, diffuse and change intensity of color from deep grays or blacks to a very faded yet darkened white. With Shadow Legacy no. 16, we are visually challenged by a combination of turning and bending of surfaces. At the same time, we are conscious of depth in the image, and the sense of a strip of shadow that seems inserted along the entire length of the image, within a circulating helix of shadow that, at the same time, seems to be one part of the same shadow — all of which does not seem possible in a “straight” photograph.

Biondo is not the first artist to be mesmerized by light. “My interest in the properties of natural light and our perception of light is one of the reasons I’m so intrigued with the work of artists of the Light and Space movement, which began in Southern California in the 1960s and emphasized light as subject,” she explains.

“This series of work is highly influenced by the work of early Light and Space artists who encouraged their audiences to look at and experience the physics and phenomenon of light in new ways. James Turrell is my favorite of the Light and Space artists because he is focused on looking at atmospheric color in new ways with his Skyspace structures and other work. His Skyspace structures play with our perception of atmospheric color, which is a main component of my work. Turrell has been described as ‘an avid pilot with a lifelong fascination in merging earth and sky.’ I’m also trying to ‘bring the sky to earth’ with my Legacy and Rayleigh series.”

© Brenda Biondo, Shadow Legacy no. 18 (2020)

Shadows have been part of vernacular and art photography since the earliest times. Edward Steichen’s Pillars of the Parthenon (1921) used shadow to define these massive columns to “convey a tangible and immediate sense of the space and scale and drama of the great construction,” as was written by John Szarkowski in his book Looking at Photographs. An 1922 image by Paul Outerbridge used shadow and light to define shape in a way very similar to Biondo’s. In this untitled image, a smooth-sided brick like form was cast in shadows, light and dark, that defined its rectangular shape and gave the object weight and dimension. Manual Alvarez Bravo in the Eating Place (c. 1940) image used shadows differently. He used shadow to hide details. Here, the faces of five men sitting at a food counter are hidden. The shadow is not defining an object as with Biondo’s work, but removing details to focus the view’s attention on the posture, clothes and position of the men on their stools. This use of shadow is not dissimilar to how Ken Josephson in Seasons Greetings (1963) allowed his shadow to roll over and surround a baby swaddled in white cloth lying on the ground. His technique with shadow highlighted and focused all our attention on the baby lying centered in the image. Many photographers use shadows, and it is an endless list with masters like Ray K. Metzker, Laszlo Maholy-Nagy, André Kertesz and others. Biondo’s work shows similarities to René Burris’ Shadow of a tree (1963). Selected by John Szarkowski in his book The Photographer’s Eye, an unseen tree causes a bold dark shadow to run spreading wide across the print, away from the viewer toward an old wall and horizon. He, like Biondo, is using light and shadow to define shape and form of an object from nature. So what is different in Biondo’s work? These artists did their work in black & white. Biondo ventures subtly into color to highlight the blueish tone of shadows at the higher altitudes at which she practices. In this, she is different from the others. With this, she has taken a new step in perception and photography, extending a well-worn path a little further.

Biondo is also an environmentalist. Her crisp high-elevation shadows remind us how the quality of light and shadow in cities is diffused and faded. Her work with shadows also reflects her view that the natural world is “essentially as shadow of its former self.” She suggests that we can “pick any barometer of the natural world, and you’ll see the huge destruction man has caused during the past few hundred years – forests eliminated entirely in many parts of the world, entire species driven to extinction, wild places transformed into cities, towns, subdivisions, parking lots, etc. Half of the earth’s original forests are gone. The world’s wildlife populations have plummeted by 68% since 1970. Etc., etc., etc.” By controlling and directing our perception of nature in her A Legacy of Shadows work, Biondo references how we’ve long controlled and constrained the world around us.

Brenda Biondo’s images mix abstraction, beauty and reality. Our enjoyment of this work is tempered by reflection, both literally and thoughtfully, with an appreciation for how our world is illuminated by light, and the shadows it creates. This is what artists do, and how they help make our world a better place. They help us see. We learn and are challenged in how we see. Our perceptions are altered, even with what we take for granted as an everyday visual event. Shadows are not the same everywhere, nor are the images created by the photographers that try to capture and tame them. The blue shadows of Biondo’s high mountain elevations are a vision apart from what a city dweller might experience and dismiss. In Sky Light, Brenda Biondo has cleverly allowed us to both look up to a “Rayleigh” sky and down at a “Legacy” of past, present and future shadows.