Before there were cameras with a glass lens, whether on a phone or any one of the many styles of “camera” available today, images were seen on walls and floors as light traveled through tiny holes in barriers between an interior space and the outside world. Before people understood how images could be captured, light entering a darkened space intrigued, amazed and even frightened early humans. Robert Calafiore has practiced the art of using a pin-sized hole on a dark, light-tight box, to capture an image on light sensitive paper. He has brought forward the most ancient of image creation traditions and reintroduced it into our digital dominated modern age.

Capturing images of our world has been a pursuit of mankind from pre-historic times. Historians point to written records of light coming through a small hole in tents and buildings creating an image on opposite walls by the early Greeks. Leonardo da Vinci explored the concept of images formed through tiny holes during the Italian Renaissance period. Ultimately, the use of a tool to capture images became a reality in the early 1800’s. The camera lucida was a device, patented in 1806 by William Hyde Wollaston, an English chemist and physicist, that projected and reflected images in such way that an artist could trace or draw what they saw. The camera lucida was a drawing aid. It was not built to permanently “capture” an image directly from nature, with “nature’s hand”, in some way onto paper. This critical step toward capturing images from nature led to the development of the camera obscura.

The camera obscura is the precursor to the pinhole camera. The camera obscura was a device, or box, without a lens, which sometimes was used with a small pinhole. The difference from the camera lucida was the way the image was projected. The image viewed through the opening in the camera obscura was projected on the wall opposite the hole within a dark box. The pinhole cameras Robert Calafiore builds, and uses, are directly related to the camera obscura. The term camera obscura literally translates from the Latin as “dark room”. It is believed by many that Johannes Kepler actually created the first practical camera obscura. The earliest permanent “photograph”, named a “heliograph”, was taken by Nicéphore Niépce using a camera obscura.

The camera obscura created the foundation for modern photography. It was this early work and Niépce’s partnership with Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre, that enabled Daguerre to develop the Daguerreotype in 1839. The Daguerrotype was an extremely detailed permanent black and white image on a smoothed silver-plated copper metal surface that opened up photography to public use and appreciation. Around 1833, William Henry Fox Talbot in England used a camera obscura to help him draw, an apparently frustrating exercise given his lack of artistic skills drawing as was expected of an English gentleman. He wanted to find a way to have what he saw in nature captured naturally, and accurately, so he did not have to create a hand-drawn image. Ultimately, around the same time as Daguerre in 1839, Fox Talbot also moved photography forward with the development of the calotype paper negative that allows for a better capture of images that could be reproduced. Fox Talbot published his calotype images in the first commercially published photography book, “The Pencil of Nature”, between 1844 and 1846, using actual photographs he had created. Talbot had succeeded in avoiding the need to draw an image. He moved the camera obscura concept forward by creating a light sensitive material that would permanently hold an image drawn by the hand of nature when chemically fixed. He even noted in this book that the images were “created by the sun”, and not by his hand with a pencil. Robert Calafiore found Talbot’s own glass still life work inspirational.

Much of Robert Calafiore’s camera obscura/pinhole style of photographic practice are color still-life imagery of glass, referred to as “Ogetti di Vetro”( which translates from Italian as “glass objects”). The glass objects selected related to his family history. As a child growing up, these objects fascinated him. These were magical and special. Glass was one of the first “luxury” things his Italian immigrant parents owned in America. In the early years, glass was only from his parent’s collection. In later years, he added his own acquisitions of glass. The new acquisitions of glass became symbolic of his own metamorphosis and change.

© Robert Calafiore, Untitled (2009-2012)

Glass reflects light in many ways. In some cases the glass is cast, and others pieces are hand blown. Calafiore also loved the glass made in Murano near Venice, and from Empoli, Italy; both centers for beautiful and delicate glass art creations. Each style of creation has its own unique characteristics. Calafiore has studied each, and uses the science of light to give depth and dimension. His images result from constant experimentation, staging, arrangement, installation and camera construction.

Why Robert Calafiore chose to use a camera obscura/pinhole style of photography is a much deeper statement about our times and society. He had been teaching for over twenty years, and about ten years ago he noticed a change in his Hartford Art School students. One of his course requirements was to build a pinhole camera. Early on, it was a grand exercise that the student easily and successfully executed. But what happened next is the story behind Calafiore’s choice of art form. “Over time, more and more of them [the constructed pinhole cameras] … failed to function as needed. They were no longer light tight. They had also become lopsided, off square, ill measured, messy and fragile. There seemed to be a lack of sensitivity to materials, a disconnect to understanding how to handle objects… also apparent, was that the communication changes between students was impacting certain abilities. Articulating ideas face to face, contributing to critiques in a commanding way, their access to information, answers, and shortcuts to research has changed the way they relate to information…The press of a single button and bam…all of what you need is flashed on your device for you.” Today’s digital world had proven how invasive technology was, overwhelming his student’s basic skills of creation and performance. Consequently, in Calafiore’s work, digital tools and technology are not used. He had learned something of great value from observing his students.

Using the old technology of camera obscura enabled Calafiore to challenge his own dependence on today’s technology, and preserve his core skills of photography. “I chose to use the pinhole camera and make work that turned in the opposite direction of new digital technologies. I wanted to look at my own relationship to the physical world and the people around me. I wanted to make work that was relevant, felt contemporary, looked high tech, but yet was made with the simplest camera to capture an image. I wanted the work to be physical, labor intensive, require strong skills in technique and craft, yet look as if it were made at the push of a button. I wanted to be deeply connected to the work by hand.” He built more than 20 cameras of different sizes and character. Each camera has its own unique features. While the operation of a pinhole seems straightforward and simple, the construction and use is extremely complex.

The style the whole camera created impacts the quality of the image as well as the length of time the light-sensitive material in the camera is to be exposed. Exposures with a pinhole camera can go from several minutes to hours. How the light sensitive film or paper is fitted into the camera affects the image. If the film or paper lays flat, the image has one quality. If the paper or negative is curled or otherwise not flat, the image is, in turn, distorted, sometimes intentionally by Calafiore, to give his images a certain appearance. In some cases, he has attached paper holders for 4”x5” or 8”x10” from old style film camera backs. Regardless, all of Calafiore’s image are made directly onto light sensitive paper, and not film. Each image is unique. There is no ability, as with a film negative, to make exact reproductions, unless the image itself is copied, which he does not do. This emphasizes his interest in the photograph as object. Each image is the only created photographic object that will exist.

© Robert Calafiore, Untitled (2013)

His images are the literal reverse, or negative, of an image as we would expect to see it. Dark is light, light is dark, and colors are recorded as approximately their opposites. This is a consequence of the photographic technique he has chosen. The image is recorded as a negative on the light sensitive paper, same as it would be on film. From the film negative, a positive image would be made by enlarging or contact printing the film. Positive contact prints could also be made from his negative images, but this body of work is about the unique negative images he creates. Calafiore, as an artist, has chosen to present his images as a negative. It causes the viewer to engage more directly with the image created. According to Calafiore: “The negative image exposes a layer or a “world” that can not be seen otherwise. This unusual view of what surrounds us, helps to drive my practice. It’s as if I am seeing something I shouldn’t or isn’t meant to seen. Something that is more than just the sum of the parts as I construct the photographs. It leaves me wanting more.” We have to stare more closely and take our time examining and processing what we see. Since the image is the reverse, we have to outline in our minds what it is we are actually looking at.

In most commercial cameras, or even with the human eye, there is a correction made to turn the image we “see” back upright for easing viewing and composing. In Calafiore’s pinhole cameras, there is no viewfinder that allows him to see the subject. He applies mathematical formulas, given the size of the camera and the distance to the subject, to determine what will be in view and projected through the pinhole onto the paper at the back of the camera.

The type of photographic paper that Calafiore is using is “chromogenic”, referred to as a “C-Print”. A consequence of a “negative” or reversed image is the change in color associated with objects in the image. Chromogenic paper contains layers of dyes, that interact with other chemicals in the paper to record the color that is radiated to the paper surface from the light reflected off the surface of what is before the camera. Mastering the ability to capture images using a pinhole camera required much trial and error.

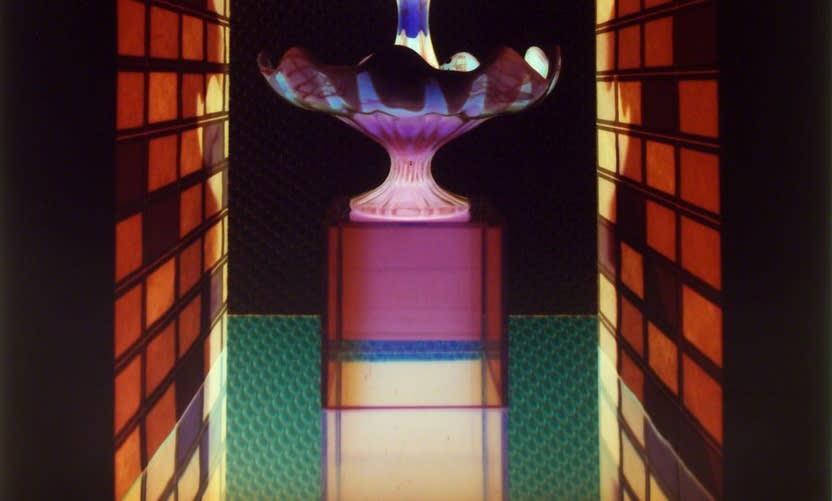

From 2009 to 2012, these unique single image prints were 30”Wx40”H. This would require a rather large-sized pinhole camera to be constructed. The style of setting up his still life images around the glass objects also evolved, as did the way lighting was positioned around the glass arrangement. In the early years, the images are not bordered, or enclosed. These appear to be set on an open table top sort of surface. The tower of glass is tall and appears sturdily built, yet delicate. Behind each tower is a color splash that indicates a light of some color shining on a wall behind the tower.

In 2012, Calafiore was thinking about his “growing-up” years, and the architecture of churches his family attended. These buildings had a very medieval, gothic and renaissance style. The five images done in 2012 are 40”Hx30”W prints of a glass tower, set on a stage with curtains on either side. The arrangements appear set in a recessed alcove with a gentle arch and straight sides. Each side wall is two-toned, giving a sense of depth to the side walls. These glass towers appear taller and more precariously balanced than the structures that follow. The sense of curvature in the side borders comes from how he inserts the paper into the camera. The paper, which is slightly curved as it is placed in the back of the camera box, affects how the light lands on the light sensitive paper, creating this visual effect.

Continuing with large scale 40”Hx30”W images in 2013, his glass towers now have two planes of focus. One in front and to one side with the other to the rear like two advancing soldiers, spacing and staggering themselves apart. Unlike the later images, these do not appear framed into a box, it is a more open setting. In some, the objects appear to be in a corner setting. In others it appears that they are sitting on a glass base. It is Calafiore’s intention that these are done as a reference to each other, and become like two people, a couple, illustrating the complexity of a personal relationship.

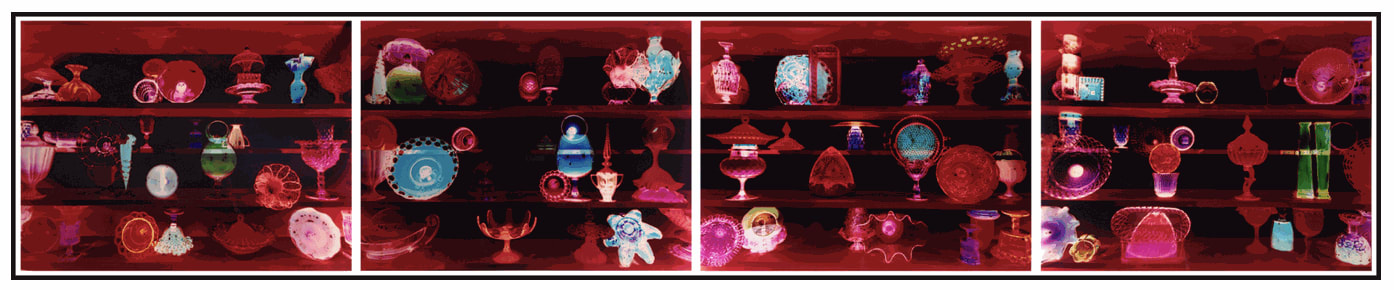

While each individual image was an object for visual satisfaction, Calafiore in 2014 and 2015 created new arrangements. During 2014, rather than building a single tower of glass, he made two images, each with several shelves, with an arrangement of glass objects with varying shapes and color on each shelf. Then in 2015, Calafiore began placing several images tucked side-by-side as one installation. One image, a four panel alignment, each image, 30”H x 40”W, is titled it “Ogetti di Vetro, Fuoco” (Object of Fire Glass”), making it 30”Hx160”W. The arrangement shows both glass on shelves and a four panel arrangement, which was very different from the single still construction images of earlier years.

© Robert Calafiore, Ogetti di Vetro, Fuoco (2014)

With this change, Calafiore’s work began to reflect the influence of one of photography’s earliest practitioners, Willian Henry Fox Talbot. Talbot’s “The Pencil of Nature” (1844-46) book included images of glass on shelves. Calafiore went on to create other installations of 3 to 21 images aligned together. “Ogetti di Vetro, Smeraldo”, which translates as “Emerald Objects of Glass”, is a compilation of 18 panels, assembled to measure 72”Hx120”W. “Ogetti di Vetro, Annebbiato”, translated as bleary or fogged object soft glass, a straight line of 6 images, each panel is 24”Hx20”W, for an installation that is 24”Hx120”W. “Ogetti di Vetro, Ambra”, Amber objects of Glass is yet another 18 panel installation, with each panel 20”Hx16”W for an overall assemblage that is 60”Hx112”W.

In 2016, Calafiore must have again constructed a new and different camera as the prints are now a 20”Hx16”W size. Here the artist is drawn to certain patterns inspired by elements he observed in the physical world. There appears to be more of a pattern in the areas around the glass and the structures appear more delicate and thinner. There is also a triptych in this series of 20”Hx48”W repeating patterns. Within these images, different colors appear, presumably from a color filter over the light. The still life scene, again with a single structure, is set in a more box like setting. The walls vary dramatically in color. Some are a uniform color. Others have a marble like swirl. The back wall changes, becoming more translucent allowing light to come through from behind. Rather than the viewer’s attention only focused on the way light reflects in and around the glass structures, we are now engaged by all sides surrounding and supporting the glass still life.

We see something new in 2017. Calafiore is changing image size again to 24”Hx20”W. Images appear to have an oculus or eye looking out at you. More movement and energy is pushed out form the frame. Other glass pieces frame the enclosure. In 2018, Calafiore’s images become smaller at 10”Hx8”W with single objects, placed on different pedestals.

Photographing glass is a unique challenge even when not compounded by the use of the pinhole technique. We can see that he has changed the lighting over the years. How the lighting is set, impacts whether the glass looks flat or has dimension. Lighting defines the shape and texture of the glass. In some cases, lights shine upward from below. The lighting can come into the image from any position; in front, the sides, or from behind. It is also possible to give a defined border to the glass in the manner of materials, solid or translucent surrounding the glass. His backgrounds change from a flat to a graduated or continuous tone. What is evident is that Calafiore has perfected his understanding of how light disperses through glass.

Calafiore also made male nude figurative studies using the pinhole camera at the same time he was working on his glass still life images. Figurative studies presented different challenges. A glass still life structure is easily kept stationary, while keeping a person still for any length of time is fundamentally more difficult. Because of the long exposures required with pinhole photography, movement blurs images. Staging and lighting the set for a human still life was an entirely different exercise.

© Robert Calafiore, Untitled Male Figurative Study (2018)

His figurative work is very different style from other photographers. His images, again made directly on photographic paper, create a “negative” of the image we see. Usually, when we look at a nude, or figurative, work, whether male or female, it is a positive image. We examine the body for what it is. There is usually little left to the imagination, with the exception of works such as the “Distortion” series work of André Kertész or the varied perceptive of Bill Brandt, which also challenges our perspective and recognition.

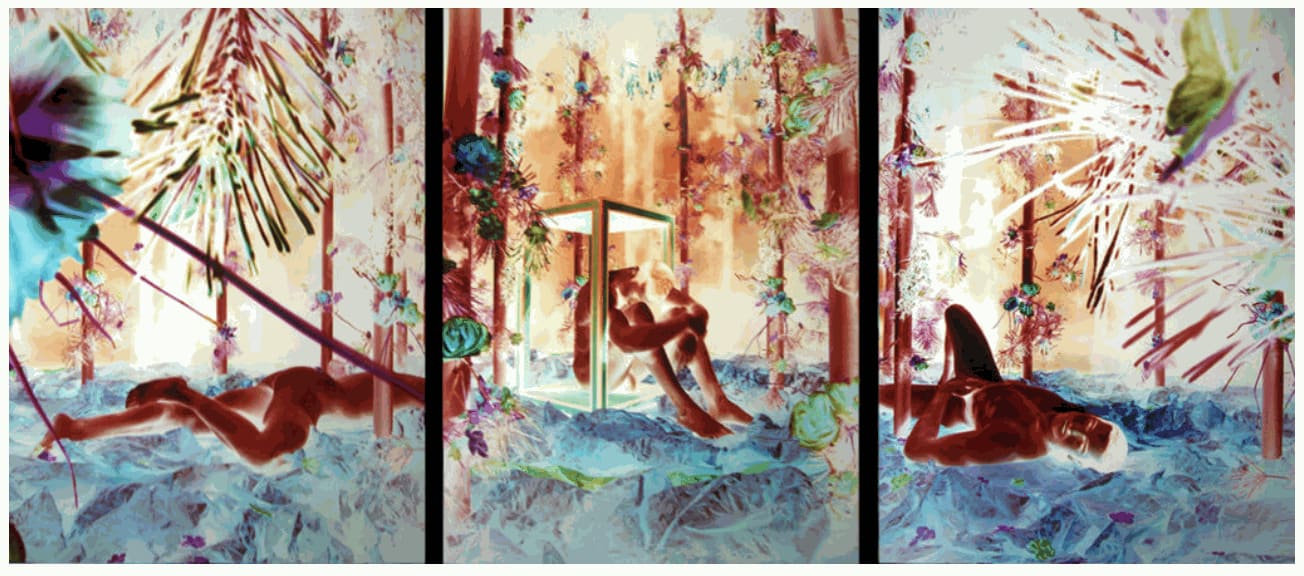

Calafiore’s images are fanciful scenes. In the figurative image to the left, surrounding the figure are plants of some kind. We assume it is a male figure. The way the figure is positioned, the viewer must carefully consider how we address gender, and if that matters. There is a wall in the background that appears to have shadows of the plants reflected upon it. The wall itself seems to be a fabric or panel-style curtain of some kind with a floor with varied color tiles or sections. The floor looks smooth and without texture. It is rigid and defined in sharp contrast to the body and the plants in the image which are anything but rigid. The man’s body lies sprawled across the floor at an angle away from the wall with an outstretched arm toward the viewer. It is unclear if the outstretched arm is a request for help, a random placement of a collapsed body, or an invitation to the viewer to bring themselves into the image.

In Calafiore’s figurative studies, one can see the influence of several artists. His careful placement and expressive positioning of the male nude was influenced by the work of George Platt Lynes. Calafiore became adept at story telling using multiple images. It is a Duane Michals style visual dialogue. With both his glass still life images and his figurative studies like the one above, he creates an interesting narrative. In the figurative triptych below, the three images are united by the setting. Each section seems to express a separate emotion. The staging and set for each of the images seem to echo what Calafiore might have appreciated in the work of Robert Cummings’ Hollywood movie sets. While one can argue what we each sense in each image, it is not arguable that some form of loneliness, contemplation, and desire for engagement with the viewer exits in each image. The pinhole effect of reversing colors is reminiscent of Barbara Kasten, whose abstract constructions and use of color was another artist he studied.

© Robert Calafiore, Untitled Triptych

Robert Calafiore’s glass and figurative still life work takes us to a special place. It challenges us to use our vision, to participate and be imaginative. We have to use our visual senses, and study each image, to translate what we see into something familiar to us. He has succeeded in slowing down the viewer. Whether by free will or involuntary compulsion, we cannot abandon any of his images until we are satisfied we understand what we are seeing. We might never be satisfied, but we are always rewarded with a sense of accomplishment when the vail of uncertainty is lifted and we can acknowledge that what we see reminds us of things, or persons, to which we can relate. Calafiore has cornered a special niche in photography. By using the earliest photographic practices, he has created a modern, very contemporary artistic expression. The simplicity of what he has done, despite the effort in experimentation to do it well, has lifted us to a higher place above and away from a digital trap. We cannot push any buttons here to be told what to think or see. We cannot search the internet to explain what we are seeing. What we see is all that there is. His literally unique artistry rewards us greatly without reliance on digital noise whispering at us, and telling us not only what to think, but what to see. With Calafiore’s work, it is just him and us, alone.