Art—once imagined, visualized, created and set to paper, canvas or other substrate—becomes a source of creativity and inspiration for other artists who may copy or appropriate those images for their own use. With that in mind, is there a limit to what we consider photographic?

Technology and the evolution of digital images has made the replication of images of all types prolific. Not only is there the re-use of a single image, but an artist may combine an entire group of images from multiple sources into a new composite work or “photomontage,” which uses any number of photographic images into a work of art, in whole or in part. Images can be sourced from photographs or non-photographic images. Whether or not non-photographic images are used in combination with photographs, the created collage or montaged work is an artistic expression.

Frequently, we hear these artists claim that they are not photographers, even though they may use photography to create their art. If an aggregation of images is created and none of the images are photographs, yet the art object itself is photographed, and the photograph is now the created art work, is it photography-based art? Is that artist to be referred to as a photographer, or do they become some other type of artist?

“Still Life, Still Death” ©Julia McLaurin 2018

In Julia McLaurin’s “Deer Head Still Life,” we have an aggregation of objects. Each flower, deer head and fruit is composed and captured by McLaurin in an image that we would readily reference as a “photograph.” We would not hesitate to call her a photographer.

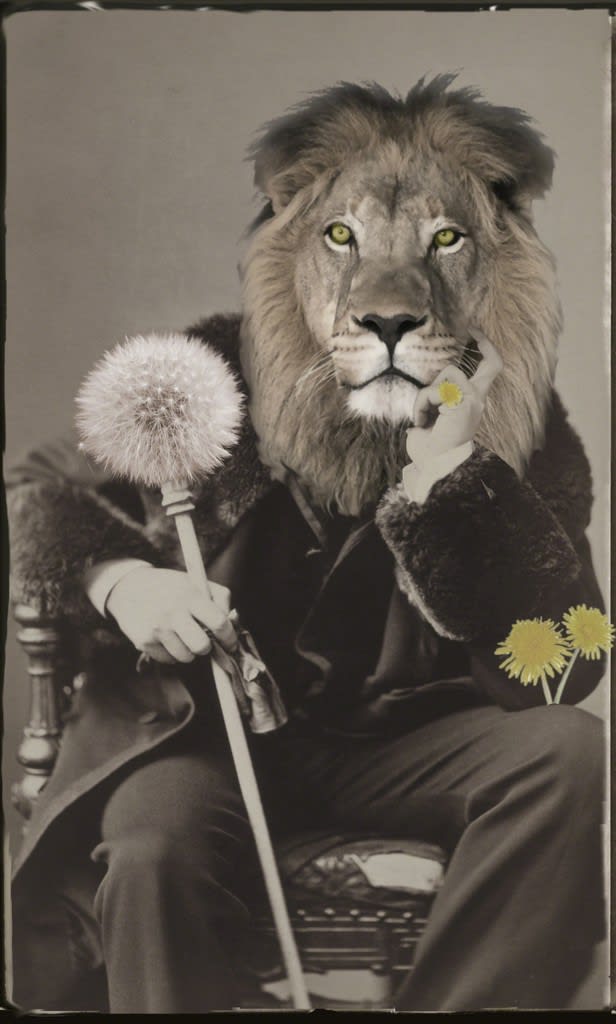

As a photographer, McLaurin takes a step away from the pure photographic image with her series “Lions, Tigers and Bears (Oh My).” She combines her own photography with found old-timey photographs of people and converts these persons from our past into “Dandy Lions,” “Tiger Farthings” and “Fancy Bears.” Since both the appropriated work and her own work are photographic, we might not hesitate to call the image “photographic” or “photography-based.” One of the most well-known photographers today is Jerry N. Uelsmann, who built his visual reputation on combining images he had taken. Uelsmann perfected his practice of combining images, into one image, in the pre-digital, pre-Photoshop® world of what is considered “traditional” photography. (1) His images are all considered “photography”. In McLaurin’s case, even though parts of the created image are her work, and part appropriated photography, the image may still be called photographic. So, would Julia McLaurin still be referred to as a photographer, or an artist using photography to create “photography-based” art?

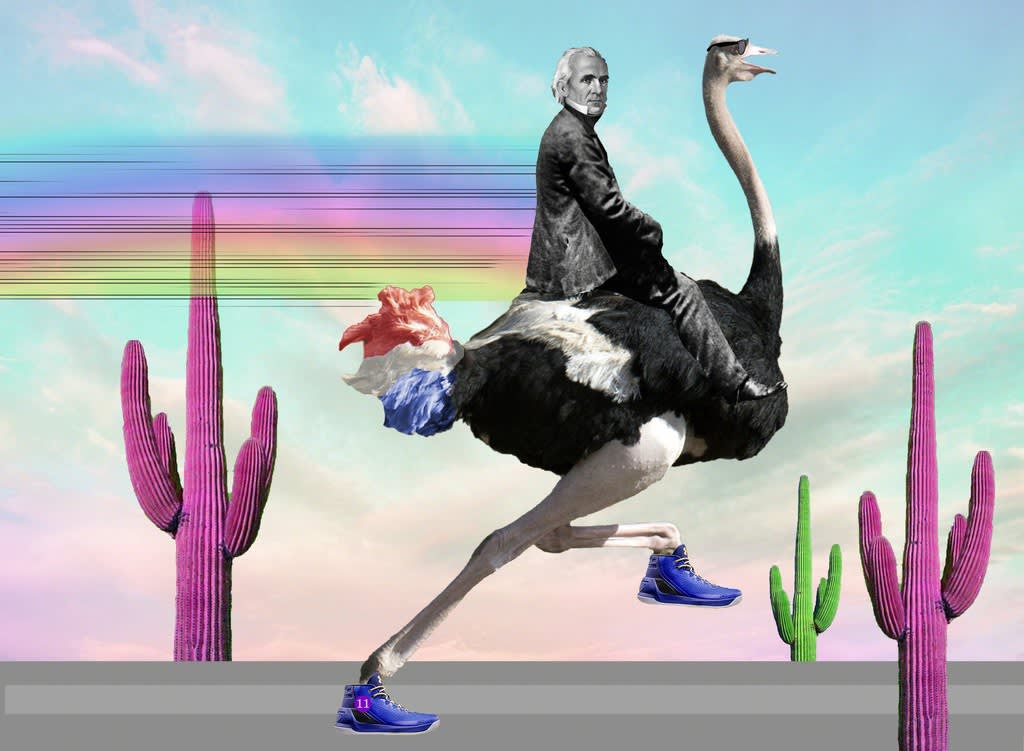

What then happens when Julia McLaurin, as a photographer, appropriates images from a greater variety of sources to create her art? In McLaurin’s new “Hail to the Chief” series about the presidents, she uses photography to capture some of the images and photographic post-processing methods to create images that are an aggregation of different images—some that are photography based and some that are not. Her imagery is dynamic, irreverent and humorous. Does that challenge the perception of what is to be considered photographic or a photography-based work?

“Dandy Lion 3” © Julia McLaurin 2018.

The institution of the presidency of the United States and the character of the person who occupies that office have received more focus in today’s political environment than in almost any prior time in history. These current issues, controversy and drama drew McLaurin’s attention. As a student of history, she studied all 45 US presidents and created a series of images, one for each president, using appropriated imagery to visually illustrate significant events from their term in office or some personal characteristic. She does not take a political side; all facts and events are fair game for her constructions.

McLaurin used photographs of the presidents in her work, where available. Photography was not made popular until the introduction of daguerreotypes in 1839, so she relied on paintings of these earlier presidents. Apparently the first photograph of a president in office was made in March of 1841 of William Henry Harrison, the 9th President. John Quincy Adams, the 6th President of the United States, from 1825-1829, was photographed later in life in 1842, a daguerreotype, but not while in office. It is said that the daguerreotype of President James K. Polk, the 11th president, taken in 1849, is the earliest surviving photography of a sitting president. Each of these portraits are formal and stern. There is no levity in these images.

President Obama is the 44th president, and the number of his presidency is on the ring on his finger. His place of birth—Hawaii—is symbolically represented by his jacket. He “quit” smoking before becoming president and hates ice cream after working in an ice cream shop. From McLaurin’s viewpoint, Obama’s glasses are a reference to Malcolm X and the civil rights movement. Many of the incorporated images may be appropriated.

In McLaurin’s image of Abraham Lincoln, the 16th president, we have the president on a motor scooter wearing a scarf, followed by a pack of dogs. Lincoln led the country during the American Civil War. In this image, the sun is at his back, and he and his pack of hounds are running forward into an uncertain place. McLaurin brings each president into modern times by embedding familiar contemporary objects of our time into the images. Mopeds were not an item during the 1860s, but Lincoln was unconventional for his time. The cool sunglasses on the pack of dogs allude to association with Lincoln as he rallied the states to the Northern cause of unity. His vision was not to have a divided America. It may suggest that today’s political climate and a sense of a divided America weighs on McLaurin’s thoughts about the role and responsibilities of the presidency.

Should McLaurin’s work be spoken about as photography-based art? What is fine art as it applies to photography-based works? The Visual Arts Cork Website provides a relevant explanation: “Known also as ‘photographic art,’ ‘artistic photography’ and so on, the term ‘fine art photography’ has no universally agreed meaning or definition: rather, it refers to an imprecise category of photographs, created in accordance with the creative vision of the cameraman.

“Abe Is Way Cooler Than You Think” © Julia McLaurin 2018.

… One might simplify this, by saying that fine art photography describes any image taken by a camera where the intention is aesthetic (that is, a photo whose value lies primarily in its beauty…) rather than scientific (photos with scientific value), commercial (product photos), or journalistic (photos with news or illustrative value). … Artistic photos have been used frequently in collage art (more correctly, photocollage), by artists like David Hockney (b.1937); and in photomontage, by Dadaists like Raoul Hausmann (1886-1971), Helmut Herzfelde (1891-1968) and Hanna Hoch (1889-1979), by Surrealist artists like Max Ernst (1891-1976), by the avant-garde Fluxus group in the 1960s, and by Pop artists like Richard Hamilton. Photos may also be incorporated into mixed-media installation art, and assemblage art.” In the early years, the collage art of the Dada movement was very much driven by political expression. Photomontage, or “photo collage” as it might also be referenced, is discussed in this context in an earlier Commentary by Foto Relevance. McLaurin is going back to the origins of photographic collage, to align not only with this form of expression but with the same driver: politics.

In an article on “Photomontage,” the website Artsy commented: “A technique best known for its close ties to Dada, photomontage is a type of collage in which photographs (either taken by the artist or sourced from mass media) are assembled into a single composition. The images may be physically or digitally combined and, in particular in early compositions, may contain text or abstract shapes. During its development in the early 1920s, bragging rights for the invention of photomontage were hotly contested, often in manifestoes, with Dadaists Hannah Höch, Raoul Hausmann, and John Heartfield in Germany, and Alexander Rodchenko… .” Many, if not most, of those images were taken from other sources, just as with McLaurin’s work.

Does the act of appropriation make a work less of an artistic expression of the artist? The re-use of images, within the genre of photography, re-rooted itself in the 1960s. MoMA describes the concept of appropriation as: “… the intentional borrowing, copying, and alteration of existing images and objects. A strategy that has been used by artists for millennia, it took on new significance in the mid-20th century with the rise of consumerism and the proliferation of images through mass media outlets from magazines to television. … Today, appropriating, sampling, and remixing elements of popular culture is common practice for artists working in many different mediums, but such strategies continue to challenge notions of originality and authorship, and to push the boundaries of what it means to be an artist. …” The issue of appropriation and the use of photographic images was made famous by Richard Prince with his reuse of the “Marlboro Man” images and by Sherrie Levinein her exact reproduction of the work of Walker Evans and other classic and well-known photographers. The perception of a photograph as fine art is challenged when it is reproducible, rather than a unique object, but reproduction has existed in many forms of art. Using appropriated images should not be a challenge to the sense of creative originality or uniqueness of expression.

With “appropriation” comes the issue of originality. Can a work made from appropriated images be an original and authentic expression of an artist? The Tate Museum discussed this issue: “Appropriation art raises questions of originality, authenticity and authorship, and belongs to the long modernist tradition of art that questions the nature or definition of art itself. Appropriation artists were influenced by the 1934 essay by the German philosopher Walter Benjamin (1892 to 1940), The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction, and received contemporary support from the American critic Rosalind Krauss in her 1985 book The Originality of the Avant-Garde and Other Modernist Myths.” In a case where images are gathered and combined from many diverse sources, the response would seem “yes,” that it is original art. The original art is separate from “mechanical” copies, because the cultural context has changed, according to Walter Benjamin. As McLaurin incorporates appropriated images into her works in the context of the current times, she is creating a work that needs be viewed in this time and space. The work becomes its own new original construction and expression.

McLaurin’s series “Hail to the Chief” should be viewed in the context of the time during which her images were made. The presidency of the United States today is under close examination. The audience viewing her work is bombarded daily with commentary, criticisms and challenges of the presidency, which has also influenced how McLaurin chose to represent each of the 45 presidents. In addition, it colors how a viewer of the work will interpret what they see in her images.

Walter Benjamin’s work on the mechanical reproduction of art, by his own argument, is taken in the context of the times during which he wrote, and his views are very relevant to how we see art today. Benjamin, a German Jewish writer and philosopher, was seeking to escape the Nazi regime during WWII before he committed suicide near the French-Spanish border. He argued in Sections II and III of his famous work The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction, “Even the most perfect reproduction of a work of art is lacking one element: its presence in time and space, its unique existence at the place where it happens to be. … The manner in which human sense perception is organized, the medium in which it is accomplished, is determined not only by nature but by historical circumstances as well.” He explains its usefulness, politically, with his references to Marx and Fascism. He wrote in Section XII: “Mechanical reproduction of art changes the reaction of the masses toward art….Although paintings began to be publicly exhibited in galleries and salons, there was no way for the masses to organize and control themselves in their reception.” By this statement, he acknowledges that the mechanical reproduction of work expands the audience that can see it, where works restricted to a gallery or museum have a limited audience. If McLaurin’s work on the presidents is more than childlike folly and is instead a more thoughtful statement, then her re-use of images is art and a strong expression of sentiment that becomes available through photographic reproduction to a broader audience.

“James Polk” © Julia McLaurin 2018.

Benjamin appreciated the power of the image. In Section XIII of his writing on art and mechanical reproduction, he commented on the power of photography and film specifically. “By close-ups of the things around us, by focusing on hidden details of familiar objects, by exploring common place milieus under the ingenious guidance of the camera, the film, on the one hand, extends our comprehension of the necessities which rule our lives; on the other hand, it manages to assure us of an immense and unexpected field of action. … The enlargement of a snapshot does not simply render more precise what in any case was visible, though unclear: it reveals entirely new structural formations of the subject.” What Julia McLaurin has done is draw our attention to the history of the Presidency. She has chosen certain facts from each president’s term in office for us to find, learn about and consider. More importantly, she is doing this in a way that allows us to examine time and events through her experiences and her eyes, filtered by the times today in which she—and we—live. The images appropriated by McLaurin take on a new originality of presentation and scrutiny compared to whenever the images might have originally been shown. These new images then become generators of thought, perhaps more so than the appropriated images had been. The photographic creation of the assemblage presents these images in a new context and with new meaning and relevance.

“John F. Kennedy” © Julia McLaurin 2018.

Artists of the “Pictures Generation” in the early 1960s, like Prince and Levine, broadened the definition of photography, broke the rules of established expectations and gave artists like McLaurin a greater freedom of photographic expression. The Guggenheim wrote: “(Richard) Prince took the radical step of rephotographing existing photographic images from ads in magazines and calling them his own. With a click of the shutter the images became his—a deceptively casual gesture that changed the rules of art, making it possible to appropriate someone else’s creation as your own. In subsequent years, Prince repeated this action using other products and fashion models. He excised out all identifying text or logos, cropped and enlarged images, and rephotographed black-and-white photos in color and vice versa.”

If McLaurin’s work is not photographic, then what might it be considered? An immediate association is that her images are, in some way, “graphic design.” The website “photographydegrees.org” wrote: “Graphic design is the art of combining text and graphics into a visual message in the design of logos, banners, graphics, brochures, etc. … Their job is to ensure that communication projects have a clear and effective message, making it both a creative and a technical job. … Photography can be considered ‘old school,’ since it has been around for well over a century. While technology has modernized the art form and enhanced the industry’s standards, the basic premise of producing images that communicate a desired message or feeling is still the same.” While that author considered photography “old school,” McLaurin’s work must be viewed as undertaken for artistic expression and not as a graphic design project.

Many current day photographers aggregate images other than photographic, but the object created is a photograph. American artist Deborah Roberts’ works are collages of well-known role models to empower young African-American girls, but they are shown as photographic work. Another American artist, Penelope Umbrico, is well-known for her appropriation of images off the internet for her installations of suns and broken LCD TV screens, iconic mountains, and other objects. This work is also considered photographic work. On an art website like Artsy, you can find many other examples of photographers using collage/montage techniques such as Paul Anthony Smith (see his “Custom & Clearance, 2018” work), Peter Beard (“Portrait of P.B. in Croc Hat, Richard Lindner, 1978”), Dominique Duroseau’s use of found images (“Unknown/Undocumented 2016 #15”) and Sara Cwynar (“Tracy(Gold Circle, 2017)”).

In today’s world of experimentation and new technologies, photographers like Julia McLaurin can embrace a broad license for the form and manner of their image creation. Her early work migrated from traditional portrait photography and still life work to photomontage. Viewing her “Hail to the Chief” series as whimsical and fanciful is a superficial approach. Within each of these images, McLaurin has taken the time to understand what each president did during their term and the actions that made them human. The creation of these 45 images, which can be viewed and visually absorbed, deserves close examination to see what is revealed. The images include expressions of war, assassination, personal tastes and events. Color, light-hearted photographs—infused with a vivid imagination but anchored in history—deserve time to be examined and for each hidden fact to be found and evaluated. What each image has in common, while presenting a different individual presidency, is the perception of one person: McLaurin. Her views and experience are colored by today’s politics, conversation, events and challenges to our society. McLaurin has absorbed all of this and chosen how to present each president and what to reflect for each one. If art is expression, this is art. If an image is captured or created using the tools of photography today, then it is photographic. The work of Julia McLaurin has taken us to “theedge of photography.”

Notes: