Day or night, the sky has always held a special fascination for people since the dawn of time. In Brenda Biondo’s “Abstracts” series, she shows us the sky differently than we have ever appreciated it before. “Abstracts” consists of three portfolios of work: “Paper Skies”, “Moving Pictures”, and “Modalities”. Biondo describes “Abstracts as…constructed abstractions centered on atmospheric color and light.” These environmental studies vary by season, place, time of day and year. Her straight photographic capture evidences a deep knowledge of the color spectrum, how light is captured and measured, and the physics of reflected light on different surfaces. She has reinterpreted how a landscape or, for “Abstracts”, sky-scapes, can be seen and presented.

With Biondo’s work, we can learn how to appreciate the many colors of the sky. It is not always blue: photographers talk of a golden glow in an early morning sunrise, and there is a popular sailor’s ditty about red skies at night, dawn and delight. Early morning light and twilight are different. Weather affects color. A shadow is not always black- it may appear purplish, defying our expectations. Think about the colors you see—or don’t see—at night. At night, it seems that everything is black and white. What causes these color changes? What does Biondo know about light that allows her to intentionally and purposely combine images of the sky at different times, places, seasons and weather conditions to create diverse color patterns of what is essentially the same subject?

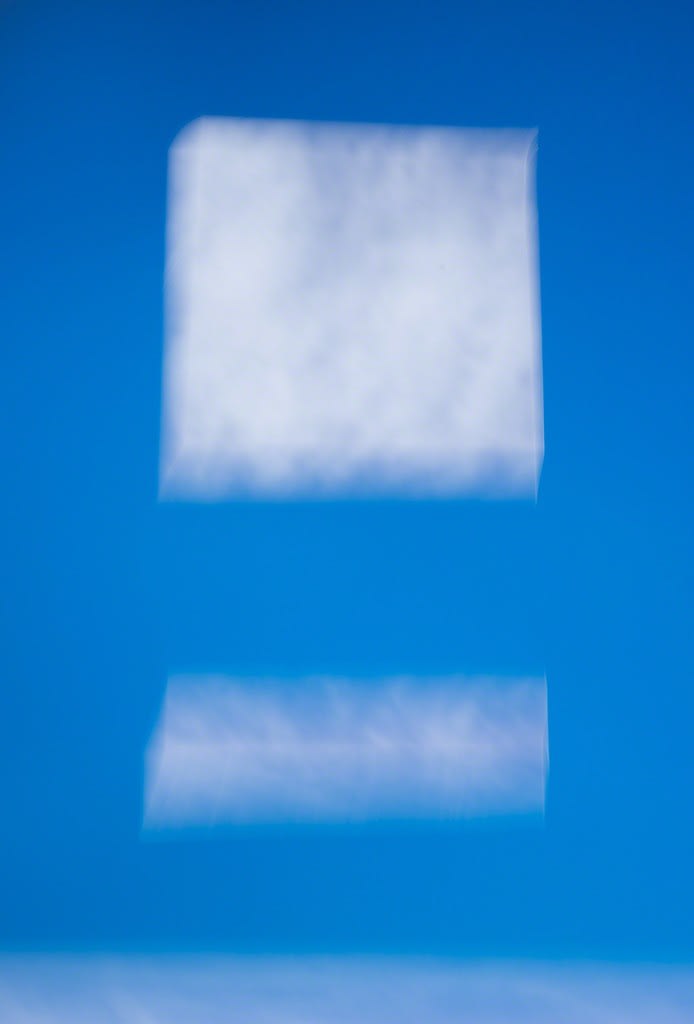

© Brenda Biondo "Paper Sky No. 21" 2016

A 1970 Time-Life book, “Life Library of Photography: Color”, explains how we see colors in the sky: “The blue of the sky is the result of … natural color separation. As sunlight passes through the atmosphere, the air molecules redirect, or scatter, the wavelengths of light at the blue end of the spectrum more than those at the red end. What we see as the sky is the blue light scattered out of the sun’s rays. The reds of the sun itself at sunrise and sunset also result from the scattering. When the sun is on the horizon, its direct rays pass through more of the atmosphere than when it is overhead. Over this extra distance, so many of the blues are scattered out of the direct rays of the sun that mainly reds are left to color the image of the sun as it reaches us.” Light appears “white” if all of the hues and wavelength that make up the light spectrum of visible and invisible light are reflected. When a color is “seen”, in simple terms, it is because all other colors of the visible light spectrum are absorbed by materials, except for those wavelengths of color that are reflected. Color is the reflected wavelengths of that part of the light spectrum humans can see.

In the morning, colors are less intense, softer. As the daylight intensifies, as the sun rises, and before it starts to set, colors are seen as deeper and more intense. This is because the various different color waves of light are more directly reflecting off various surfaces. A cloud cover or fog will reduce the intensity of the wavelength and, hence, the colors. Photographers know that the golden glow of early morning sunrise or setting sun can last only minutes, disappearing as quickly as you realize it is there. Knowingly taking a photograph at different times of day and using this knowledge of light can set a mood in the image; how we feel in the earliest light of morning is different from a scene illuminated by a cloudless bright midday sun. Biondo’s images are not as much about mood as they are about color and abstraction. Her images are not of place, but of the condensation of time and space as defined by color. The color of the sky is different, as we have said, at different times of day, in different seasons, with different weather conditions, and in different places, high in the mountains, or down at sea level. Combining any of these factors affecting light is making time and space visually condense into one experiential moment.

Biondo believes that truth in color is important. Why is it so very crucial to Biondo that these images achieve the same purity of color in her prints as she sees in nature? This artist has set a high standard of excellence and commitment for herself. After all, the truthfulness of a work’s color palette presented by an artist to the viewer is whatever the artist wishes it to be. It is only the artist that knows whether the color presented is an accurate reflection of what he or she has actually seen. It is only the artist that realizes if the color of the moment in the sky was accurately captured on the film or the camera sensor. It is only the artist that knows if the color captured is accurately and truthfully reproduced on the printing surface – whether paper, metal, or another material. If the viewer is not in the same place as the artists at the exact same moment, then how does he or she judge how well the artist has faithfully reproduced the natural scene they are seeing? In her images, Biondo strives toward making the color an accurate reflection of what she has seen.

How does Biondo recreate the blue of a perfectly clear sky? Living at 6500 feet in the mountains of Colorado, Biondo experiences a clarity of sky and color most city dwellers cannot imagine. It is this very environment that set her in pursuit of capturing an accurate replication of color, and it is this visible shock at the variety and intensity of color that make her prints important and compelling. How could she memorialize the most perfect blue or the oranges and reds of a sunset? One might argue that the accuracy of a color is less important than the visual composition and intent of the artist—but this accuracy is Biondo’s intent. It is what drives her. For Biondo, truth in color is essential.

In a way, Biondo’s “Abstracts” is a modern day recreation of Alfred Stieglitz’s “Equivalents” photographs of the sky and clouds taken between 1925 and 1934. Dorothy Norman, in her 1960 book Alfred Stieglitz: An American Seer, quoted what Stieglitz said his cloud images meant to him: “What is of greatest importance is to hold a moment, to record something so completely that those who see it relive an equivalent of what has been expressed.” While his images were in black and white, Stieglitz wanted his images to represent his competency in capturing an image, creating a composition reminiscent of a score of music and reflecting the chaos in the world and man’s “eternal battle” to tame it. Branching away from Stieglitz’s style of conveying a sense of music and controlled chaos, Biondo’s approach works to synchronize two moments in time.

Stieglitz advocated photography as art. He emphasized the Pictorial method of making a photograph appear more like a painting, and sought to have photography viewed as a legitimate form of artistic expression. Consider that more than 90 years later, Biondo’s “Abstracts” have a painterly look in line with Stieglitz’s, albeit by way of a very different technique.

Biondo is a student of art. She has embraced the influence of other artists, of all genres, in how she has learned to “see” the world. The image “Paper Sky No. 21,” for example, is reminiscent of the work of Georgia O’Keeffe (who was, coincidentally, the wife of Stieglitz), such as O’Keeffe’s “Light Coming on the Plains No. II” or “III”. Both Stieglitz and O’Keeffe seem to influence Biondo’s work, but in very different ways. Stieglitz and Biondo shared a gaze to photographing the sky and clouds; Biondo’s appreciation of O’Keefe’s style influenced how Biondo imagined and captured the bends and shapes of light in her prints. O’Keeffe, seeking her own voice, was an amazing and forward thinking female artist in her time with abstraction. Like O’Keeffe, Biondo embraces a western landscape, although O’Keeffe in arid New Mexico and Biondo in the bright, clear-light elevations of Colorado.

Biondo’s images are straight photography. While painterly, her style is not quite the romantic pictorial style that Stieglitz and his Photo-Secession movement had encouraged. What is meant when we say “straight” photography? It is an image that is not manipulated when the image is taken, processed or reproduced/printed. Biondo uses a standard digital camera, with no filters on the lens to specifically capture or deny any part of the light spectrum. The camera’s sensor is not intentionally adjusted with a bias toward one end of light’s wavelengths. When Biondo works on her images, she does not “photoshop” the image to change the colors or the composition produced in the camera, other than perhaps some basic cropping of the image. When printing her images, Biondo’s intention is to create a faithful reproduction of the sky as she saw it, and as was captured by the camera. Hers is a “straight” photograph technique in that she takes what she sees and conveys this imagery faithfully, not only through the camera lens, but also through to the printing process onto a printed surface for a viewer to see, study, critique, and appreciate.

If this is straight photography, then how are such different colors of the sky contained in one print? Biondo starts with a photograph of the sky that is printed. This print becomes the stage on which a second look at the sky is placed. The second image could be taken later that day, the next day, next week, the next month, or year. This methodology is the basis for all of the “constructed abstractions centered on atmospheric color and light.” “Paper Skies” are images where the first image is held still. In “Moving Pictures”, the first image is moved and shaken. With “Modalities”, there is a combination of multiple images from the “Paper Skies” and the “Moving Pictures” work.

In “Paper Sky No. 21,” the image may have been taken during a red morning sunrise. In all her created images, Biondo holds the first printed “sky-scape” at arm’s length and shoots the second sky through or around the first print. The first image may be cut, folded, wrapped into a tight circle, held still or shaken. What happens next is the magic of light and reflection: the colors of the first image become part of the second, and the reflections of those colors are captured creating yet different shades and hues of the first color. In addition, the second sky color is seen. In “Paper Sky No. 21,” the sky in the second image is a beautiful clear blue. In other images, we may see white and grey clouds around or through the first paper’s cuts and folds. There are shadows, too. As the first paper is cut and folded, the new light on the second day, whenever that is, then creates a shadow from the folded or cut and bent over portion. As Biondo describes her process: “All images in Paper Skiesand Moving Pictures are created by re-photographing a folded and/or cut print of a sky image (grey clouds, blue sky or sunset close-up) in front of actual sky. (There is no post-production manipulation.) In Paper Skies, the juxtaposition of the print against the actual sky creates an abstract image that emphasizes the ambiguity between the real and the reproduced, and allows the original printed photograph to be seen in a new context as a three-dimensional geometric form.” To the extent light reflects off the first image back onto the rolled paper tube, or folded paper and its shadow, new color variations appear. Combined, the second print becomes a pure and naturally-created abstraction that could not otherwise have been visualized by us.

What is magical for us to appreciate is that two very different moments in time are captured, at once, in a single image. Photography is known for capturing a single “decisive moment.” Biondo has succeed in compressing and documenting a span of time. Each of her images are two points in time that are that are non-consecutive and unrelated to each other. “In an age of exuberant digital manipulation,” she says in her artist statement, “I want to show viewers what can be revealed by simply photographing a piece of printed paper held aloft. The mysterious optical illusions, the color-mixing that is a function of time passing, and the novel combinations of shadow, line and color compel us to consider how common subjects — and photographs themselves — can be experienced in innovative ways.”

Biondo’s layers of paper, in some cases, show the influence of a James Turrell “Skyspace”. Turrell is another artist that has influenced how Biondo thinks about light. She rolls paper, holds it at arm’s length, and points the camera in such a way that we feel we are below a hole, or oculus, in a ceiling through which we see the sky above. Surrounding that hole are a variety of colors. This experience is very similar to standing in a Turrell “Skyspace” installation: new colors appear from the prior sky image reflected on the second, and the light coming through the hole lightens or darkens the color of the paper. “Paper Sky No. 27” illustrates this Turrell-like effect.

© Brenda Biondo "Paper Sky No. 27" 2015

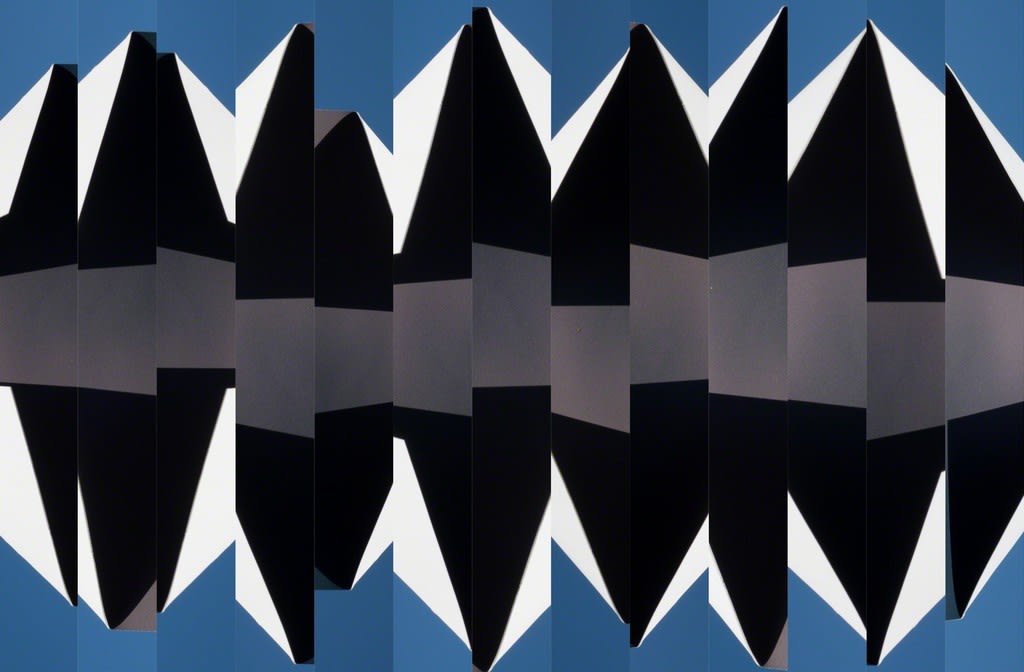

Mark Rothko is yet another artist who has influenced Biondo’s work. This manifests itself in certain images within her “Moving Pictures” work. Biondo explains: “Moving Pictures also looks at the photograph as object, but this time as an object in motion interacting with its environment over time and, in the process, literally blurring the line between what is real and what is reproduced. The images are created by quickly moving a folded and/or cut printed sky image while it is being re-photographed outside.” In “Moving Picture No. 10”, we see how Biondo took an image of a clear blue sky. She then cut a square and a smaller rectangle out of the print. At a later time, she held it up against a cloudy sky and shook the paper. The effect looks eerily similar to a Rothko image where he blends and layers paint and colors so there are no sharp, defining edges as colors merge into each other. Similarly, there are no sharp edges in Biondo’s “Moving Pictures” series. The line between what we believe is the sky and what we then see as a white area are clouds, very softly presented. One can look at Rothko’s 1954 “Painting #9 (Dark over Light Earth),” or even others he created, to see the similarity. The motion that Biondo creates conveys a special sensation to the viewer, yielding a visual soft-spoken action and depth in the image. “Moving Pictures” allow two periods of time to better blend into a feeling of one moment, rather than two moments in time standing in stark contrast to each other—together, yet independent. In “Moving Pictures,” Biondo asks two moments in time to gently and lovingly embrace.

© Brenda Biondo "Moving Picture No. 10" 2016

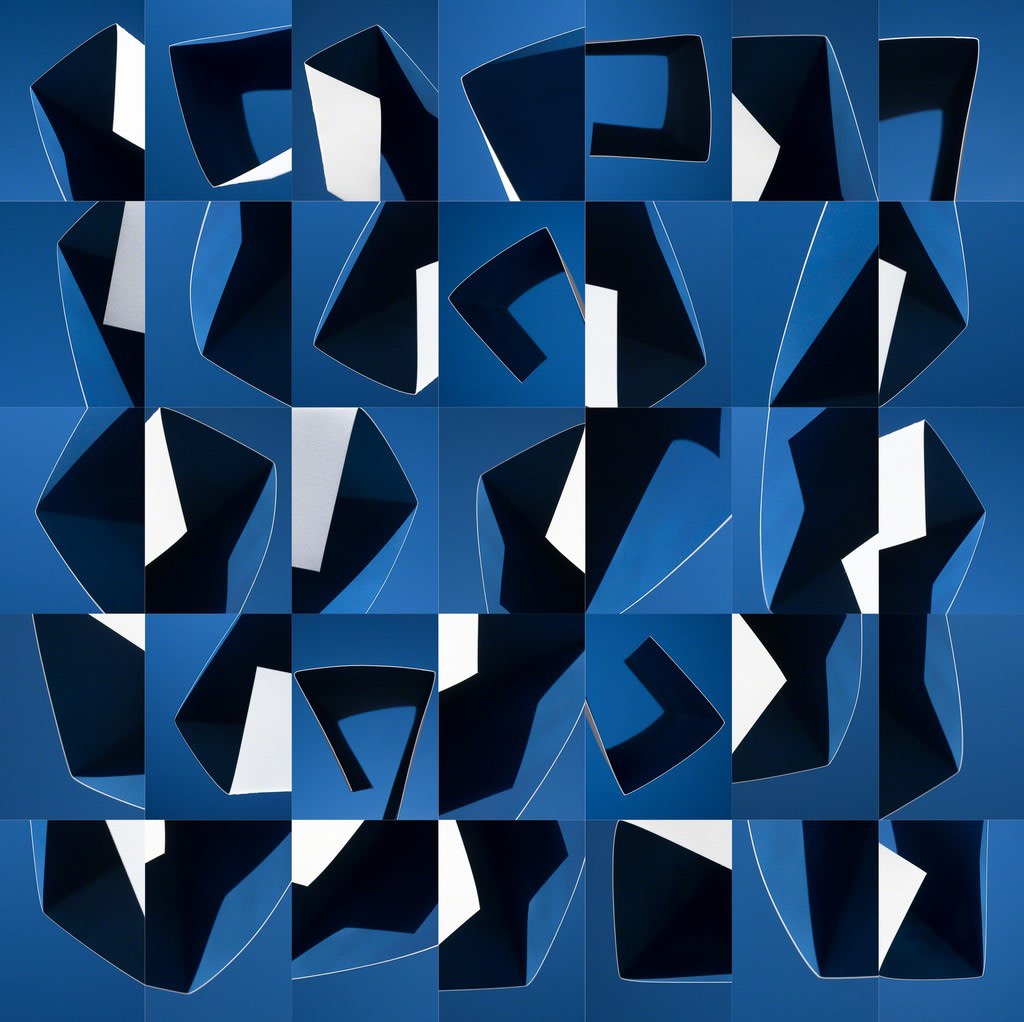

Whereas Biondo’s “Paper Skies” and “Moving Pictures” creations are singular images, her “Modalities” series involves taking several single images and combine them, side by side, in a mosaic pattern. “Modalities”explores the creative process behind a photographer’s practice through re-contextualizing similar images. Each finished “Modality” piece is a digital montage composed of outtakes from the hundreds of images shot during the creation of one of the “Paper Skies” images. An on-going series, Modalities tells a visual story about a photographer’s intent and decision-making in the course of realizing a finished artwork, and also explores the way a single subject can be re-imagined in multiple ways. With these, as with others, you can also sense the inspiration of Ellsworth Kelly. His use of color, minimalism and defined shapes resonates in Biondo’s prints. One could compare Kelly’s “Meschers (1951)“ or “Cité (1951)” work to Biondo’s “Modality No. 7 (2017)” or her “Modality No.1 (2016).” As in Kelly’s works, Biondo nods to an appreciation of Hard-Edge Painting and Geometric Abstraction influences, with the exception that what occurs is the result of nature and natural light, and not post-processing manipulation by the photographer. What occurs in these images is a testament to the knowledge of Biondo regarding how photography works, how light and color interact, and how everything is mechanically captured to be shared with the viewer.

© Brenda Biondo "Modality No. 7" 2017

Biondo seems to have wrestled and held firm to a new approach toward replicating the colors of the sky. We gaze upon her work, surprised that she is using straight photography without post-processing, for the hue of color that Biondo captures for us is beyond imagination. While Biondo’s “sky-scapes” echo the style and approach of other artists such as Stieglitz, O’Keefe, Kelly and Turrell, they are unique in their own right. Other photographers have sought to abstract the sky and landscape with photography and set a mood with color, but not in the same way as Biondo. She has reinterpreted what a sky-scape can be and how it is shown. Her photographs step beyond the usual visual capture, whether in black and white or in color, of the sky and land that photographers have made since the earliest days of photography. With Biondo’s “Abstract” series, a photographic object is created that challenges our understanding of the colors in the sky. After viewing Brenda Biondo’s work, gazing at the sky will never appear the same.

© Brenda Biondo "Modality No. 1" 2016