“The question is not what you look at, but what you see.”

— Henry David Thoreau

While Henry David Thoreau, (1) an early American writer, was never a photographer, his expression about “seeing” resonated for Michael Borek as a touchstone for capturing images. Michael Borek (2) is a photographer from Prague in the Czech Republic who emigrated to the US in 1992. While at Fotofest in Houston, Texas, in March 2016, he presented two portfolios of his work: “Treachery of Images” and “Scranton Lace”. Growing up under communism in Prague, Borek, in his words, said he felt like he carried into his images a somber overcast. He also expressed that another Prague photographer, Joseph Sudek, significantly influenced his work. This sense of history begged an examination not just of his current portfolio, but also some selected work that was created earlier in his career.

Borek’s “Tree- #5290 (Prague) from his series “Wide Asleep/Half Awake” might echo one Sudek’s images. It is no coincidence that Borek was influenced by Joseph Sudek. Borek commented that as a small boy, he once saw Sudek carrying his camera down the street, and that Sudek’s images of their shared city hung in his memory. Joseph Sudek (1896-1976) was well known for works done in the privacy of his studio. “One of the windows in his studio framed a garden with a bent apple tree, the other a garden patch leading to a wall of tenement buildings. From inside the studio, Sudek would turn his camera towards these windows, perceiving them as a source of inspirations and expressions of an “inner world” of emotion. … Sudek’s window photographs exemplify simplicity, yet are daring in their complicated relationship with the camera lens, which observes beyond the glass and acts as a constant mediator between outside and inside”. (3) This tree in Prague, captured by Borek, reflects a somber mood similar to the Sudek tree image Maia-Mari Sutnik had written about in her article about Sudek. In Borek’s image, two separate planes are created as the condensation of water in the lower third of the pictures defines the inner space, and the tree against the gray sky, clearly on the other side of the window pane, another. Borek’s image radiates a simultaneous sense of the inside warmth of the room against the cooler air outside winter-like sky. Indeed, Borek’s image “Tree” moves the viewer back to a place like Sudek’s studio. (4)

Borek’s image “Red Leaf #7668” from the later Scranton Lace series is again a somber image . Milena Kalinovska, while at the Hirshhorn Museum, had written: “Michael Borek’s Laceworks photographs were shot in a ghost-like atmosphere of a decommissioned factory in Pennsylvania. With laces still in the looms, chairs on the stage of the company’s theater, the images capture dissonance between quiet beauty and troubling reality.” (5) In this subdued image there is a gentle pallet of color. While we often see “nature” images in fall colors, this one brings the viewer in because of the unusual background that diffuses the image around the leaf. One might imagine a touch of Saul Leiter or Eliot Porter, even though they are very different photographers. Scranton Lace is about a factory that closed “…105 years after the company was founded in Scranton, Pennsylvania, in 1897. At its heyday, in the early 20th century, Scranton Lace employed over 1,400 people. Its looms, made in Nottingham, England, stood two-and-a-half stories tall, were over 50 feet long, and weighed over 20 tons. At one time, Scranton Lace had bowling alleys, a gymnasium, a fully staffed infirmary, and a staff barber. It owned its own cotton field and a coal mine. Its clock tower was a city landmark.” (6) The invasion of the leaf into the factory space taken with the dying color of fall seems an appropriate visual for the downside remanent of an economy and a business.

In that series, Borek also produced “The Scream – #7465”, another image that was very different from his other work, and very un-Sudek like. Very few of Borek’s images show people. In this image, it is Borek himself, in performance, on site at the factory. While he waited for the appropriate light to enter the factory, very much what Sudek did in his images in St. Vitus’ Cathedral, the emptiness of the factory appears to have taken a Kafkaesque hold on Borek. Borek did comment that he appreciates in Kafka’s writing, yet another former Prague resident, the author’s sense of alienation, absurdity and dark humor. None of Borek’s other images reflect this sort of personal involvement in his work. However, the primal scream in this image fits well with the emotion and expression of the Scranton Lace series, almost as if Borek was substituting himself for the frustration felt by all the suddenly displaced workers that had followed in the footsteps of earlier generations of family and friends working at a factory. Suddenly the factory was no longer operating because of global market forces beyond workers’ control and vision. Borek, shooting the image through interior windows, makes that all visible. Aligned with the other images in this series, it tells the story. This one image is an unique expression when compared with similar works by other photographers of the all too common abandoned factories found in cities in the Northeast and Mid-West.

The economic distress and somber mood captured in the “Scranton Lace “ series was also seen in another image, “The Eye – #1623”, also taken in Prague. While part of another series, “Urbania”, this image was again evidence of what was once there. It appears to be a security camera that Borek captures in a very “dead-pan” surrealistic way. The “Eye” is strikingly addictive because it suggests a story beyond what is literally seen. We have to wonder what this camera “eye” saw, recorded, and whether all those images are still available somewhere? Who and what was recorded? Do the long rust stains suggest a period time and a weariness for watching, and recording a memory of events for which no one is accountable any longer? In fact, we don’t know if we are still being watched and recorded. Perhaps, it is still monitoring, with no one, in turn, monitoring what is in some databank. How many other locations have an “eye“ doing exactly the same thing? The “Eye” has a surrealist component. Surrealism was “… a 20th-century art form in which an artist or writer combines unrelated images or events in a very strange and dreamlike way”. (7) Surrealism may in fact be a consideration in Borek’s work. While Sudek was not a Surrealist, Borek also admired another photographer, Eugene Atget. The Surrealists apparently embraced Atget’s work. “In Atget’s photographs of the deserted streets of old Paris and of shop windows haunted by elegant mannequins, the Surrealists recognized their own vision of the city as a “dream capital,” an urban labyrinth of memory and desire.” (8) When combined with Borek’s interest in the writer Franz Kafka and the artist Rene Magritte, one can imagine the “Eye” as something other than just literally the image of a security camera on a weathered wall.

Borek’s most current body of work, “The Treachery of Images”, he explains, was a photographic expression of Rene Magritte’s painting, “The Treachery of Images”, an image of a pipe with the words “Ceci n’est pas une pipe” (“This is not a pipe”) painted below. Inspired by Magritte’s work, Borek looked for familiar scenes and images on the sides of buses in Washington, D.C. Magritte was not a photographer, but apparently did use photography to help with what he did paint. (9) Part of the Borek’s latest series is about different images of the White House seen on the side of buses moving around the capital city. Mark Jenkins of the Washington Post wrote: “There are 16 pictures of the president’s home in “Treachery of Images: The White House,” … Yet it could be said that there’s only one. Each picture of the landmark is identical; what differs is the backdrop on which it has been — what? Projected? Reflected? Superimposed? The Czech-born Bethesda photographer would prefer that viewers solve the puzzle for themselves, although he does specify that the overlapping is not the result of computer or darkroom trickery. The White Houses seen on the sides of 16 white vehicles — buses? vans? — were all captured in a single shot. They’re distinguished only by minor industrial or environmental differences, such as drops of rain.” (10) As a cropped image, we think we are just seeing an actual photograph of the building, until we look closer at the image. It is then we notice space separating the metal sections of the bus, or a reflector, or a gas access port. Borek argues that these uneven surfaces, and layers in the surface of the image are what create his artistic and surrealistic expression in these images. Surrealism was a movement in photography that influenced photographers that Borek studied. “Photography came to occupy a central role in Surrealist activity. In the works of Man Ray … and Maurice Tabard …, the use of such procedures as double exposure, combination printing, montage, and solarization dramatically evoked the union of dream and reality. Other photographers used techniques such as rotation … or distortion … to render their images uncanny.” (11)

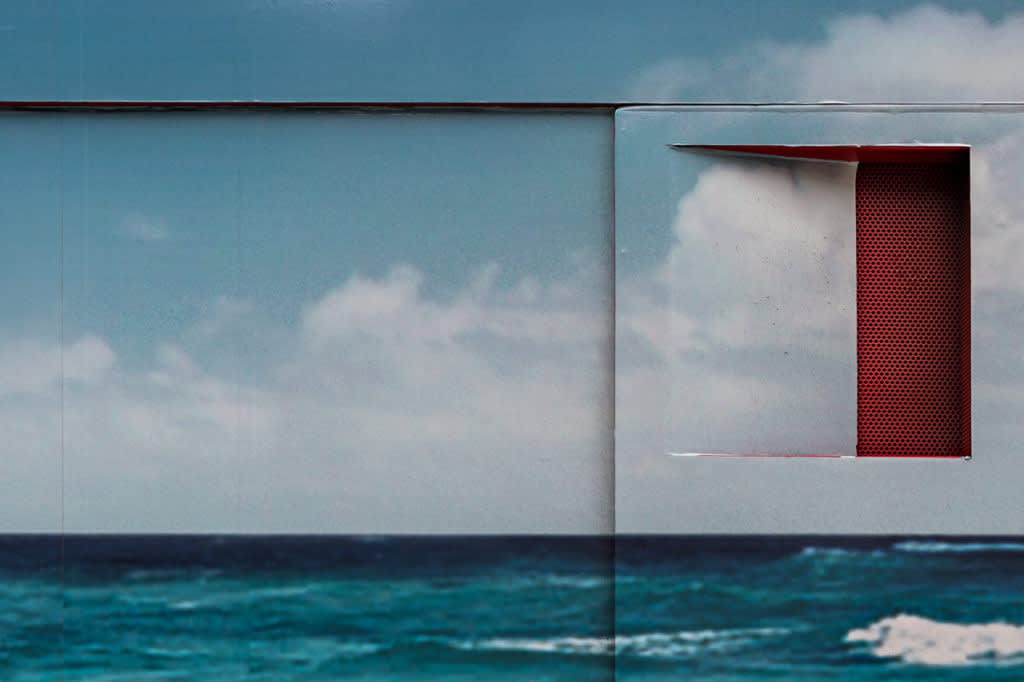

For Borek, the seascape off the side of a bus, as with the White House images, fit with the same theme. It’s the type of image where the viewer does a second take because there is tension created in the surface of the image. It’s immediately recognized as a seascape, but then we notice the vent on the right and the partitions in the image. The viewer has to question what is seen and why the photographer is choosing to make us look at this image? For Borek, its “truth in images”. It’s what Magritte tried with his painting, “The Treachery of Images”, that Borek expresses as a photographic work. The repetition of the image also tests the viewers ability to see small changes in the image surface and details that make each a separate distinct image. Like the “YouTube” excerpt of a scene from the movie “Smoke” (12) that Borek pointed out, the protagonist takes a photo everyday on the street in the same spot. In showing the photos, the protagonist in the movie explains, if you don’t see little changes, then you are not looking.

Michael Borek has his own view of the world around us, yet, he freely talks about other photographers, artists and writers that influenced that view. It was an opportunity and a challenge to look for and examine those that Borek said had influenced his work. He considers that the artistic result gives the viewer a “taste of rebellion, playfulness and interest”. This artistic expression are the layers and uneven surfaces that are internal to Borek’s images. Ironically, Sudek, who Borek idolized, was asked: “ “ Is Photography an Art?” Sudek answered: “It isn’t. It’s a nice craft requiring a certain amount of taste. It can’t be art, because it depends entirely on things that already existed before it and apart from it, that is, the world around us.” (13) Photography is art; Alfred Stieglitz fought that battle much earlier for this visual genre. Regardless, any image such as those by Michael Borek, that draw our attention and examination is an opportunity to know more about the world through the window of different eyes. Michael Borek has demonstrated to us something important: that we are not honest if we don’t examine those people or events that made us who we are, even as we strive to be unique and to create something new.

Notes:

- A quote from Henry David Thoreau, from his journal (see here: http://www.theconcordwriter.com/Thoreau_Quotes.html ) used by Michael Borek in describing his work on his website.

- http://michaelborek.com/home/

- “In the Studio, In the Garden: Variations of Light and Magic” by Maia-Mari Sutnik. See pages 265 and 267. An essay in her text “Joseph Sudek: The legacy of a Deeper Vision”. Edited by Maia-Mari Sutnik, 2012 , Hirmer Verlag GmbH (Munich) – publisher.

- Op Cit., Sutnik on Sudek, see images on Page 27 to 35. “The Window of My (Sudek’s) Studio”. 1940-1954

- Milena Kalinovska, Hirshhorn Museum, from http://michaelborek.com/portfolio/?album=1&gallery=8&galname=SCRANTON%20LACE . Kalinovska has Czech and Russian ancestry…She was director of public programs and education at the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden in Washington, DC from 2004–2015.

- http://michaelborek.com/portfolio/?album=1&gallery=8&galname=SCRANTON%20LACE

- http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/surrealism

- Surrealism-from the MET ’s Heilbronn Timeline of Art History at

http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/phsr/hd_phsr.htm - “Photographing the Impossible “ by Liz Jobey re Tate Liverpool’s exhibition of Rene Magritte’s work and Photography. FInancial Times, June 11, 2011. “It would be too simple to say that Magritte used photographs as a source for his paintings. Sometimes there is a direct relationship, as in the photograph called “The Destroyer”, in which Scutenaire, dressed as a hunter, poses for a photograph that would become the 1943 painting, “Universal Gravitation”. Or, for the 1937 portrait of his English patron, Edward James, called “The Pleasure Principle”, Magritte commissioned Man Ray to produce a series of photographs to his explicit specifications. But these were rare examples.”… “Magritte’s photographs had never been shown in his lifetime, and it wasn’t until 1978, when 62 of them were published in a little book entitled The Fidelity of Images (a conscious nod to the famous “The Treachery of Images”), put together by Magritte’s longtime friend and collaborator Louis Scutenaire, that they were seen in public for the first time.”

- Article in The Washington Post By Mark Jenkins April 30, 2016

- Surrealism was officially launched as a movement with the publication of poet André Breton’s first Manifesto of Surrealism in 1924. See http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/phsr/hd_phsr.htm.

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JGV_h36uZ5E

- “Sudek the Outsider” by Antonin Dufek, an essay within “Joseph Sudek: The legacy of a Deeper Vision”. Edited by Maia-Mari Sutnik, 2012 , Hirmer Verlag GmbH (Munich) – publisher, Page 243