Alia Ali uses a global palette of fabrics and photography to map culture and history. She is a US multimedia artist, photographer, and a global traveler with a Yemeni-Bosnian heritage, who is fascinated by the use and meaning of language and the patterns of hand woven indigenous fabric As Ali expresses it: “Textile unites and divides us, both physically and symbolically.” Her art reflects on the politics of borders, colonization, language and the non-verbal passage of traditions and cultural stories through fabrics created by master artisans from around the world. As a purposeful artist on a mission, Ali has made a concerted effort to meet the craftspeople who create these fabrics. She has traveled extensively to learn about meaning and processes associated with the fabric, patterns and pigments. While the fabrics are regional, the appreciation and production has become global. In BORDERLAND, the series originates in Yemen. In FLUX, in Côte D’Ivoire, MIGRATION in Senegal and in FLOW, Uzbekistan. The INDIGO series highlights a natural blue color used by many cultures and the حب (ḥub) // LOVE series is a fabric of Ali’s own creation, using the Arabic word for “love.” As an artist, Ali conveys all of this through non-verbal imagery that speaks loudly of these underlying currents. On the surface, these may plainly look like an exciting colorful presentation, but what is covered and explored in the exhibition “Cartographies of Pattern” is a deeper journey, guided by Alia Ali’s imagery, into the story behind each threaded weave of her BORDERLAND, FLUX, MIGRATION, FLOW, INDIGO and حب (ḥub) // LOVE series.

©Alia Ali, BORDERLAND Series, 2017, pigment print with UV laminate mounted on aluminum dibond in black wooden float frame, 42 in x 28 in // 107 cm x 72 cm, 13.5776° N, 44.0178° E, Edition of 5 + 1 EP + 1 AP

Alia Ali’s journey began with the BORDERLAND project around 2015. These images are a pigment print with UV laminate mounted on aluminum dibond in a black wooden frame. It is here that Ali begins to describe her sense of people, and begins her non-verbal critique with viewers of how humankind creates barriers and uses our unique cultures and characteristics to divide. As Ali describes it: “The term “BORDERLAND” is most commonly referred to as the crossroads where nations collide. It is a porous zone that diffuses outward from an artificially imposed human-made punctuation called a border.” In Borderland, Ali wraps her models in fabrics that are from particular geographic regions, created by artisans in this artwork. The fabric completely covers the person beneath. She refers to these models as “-cludes.” “-Cludes” is not a word by itself, but an add-on to words that carry a meaning to include or exclude. We are shut out from seeing who is enclosed in the fabric and imposing our pre-programmed biases. Our attention is solely on the fabric, so we concentrate on that, unhindered by any bias from actually seeing the person beneath. We can wonder whether Ali uses sitters with regard to their gender, or ethnic or racial identity to sit for her in the posture they assume. In each of these images, in any of these five bodies of work, the posture is a revealing expression of an emotion through these silhouettes of people wrapped in textile. This is a recurring theme for Ali. A sense of non-verbal lore passed down through generations in a tradition of pattern in fabric and craftsmanship. A sense of mysticism from the ancient past that is an element of identity of a people carried into the future. The sense of place and land in the patterns where borders are defined and separated create different identity and hence different patterns. A pure form of body language.

©Alia Ali, Avian Blush, FLUX Series, 2021, pigment print with UV laminate mounted on aluminum dibond in wooden frame upholstered in wax print sourced from Côte d’Ivoire, 49 in x 35 in x 3 in // 124.5 cm x 89 cm x 7.5 cm (framed), Edition of 5 + 1 EP + 1 AP

Why Borderland? Ali is sensitive to a fabric’s origin and history. BORDERLAND’s fabrics are a visual reminder of the vibrant trade routes and exchanges that occurred through time and people. What has happened to fabrics created by indigenous masters under prior periods of colonialism and appropriation in today’s global electronic economy influences Ali’s art and messaging. She describes it this way: “Fabric, ancient in its invention, is archival with the passage of time. The fabric, like the human beneath it, or the border it symbolizes within this body of work, is also vulnerable to the elements and to time. When all is said and done, borders shift and textiles disintegrate, but if well preserved and nurtured with culture, knowledge and grace they remain intact.” An early image in the BORDERLAND series, has a very personal meaning for Ali. The judge’s gown with traditional (Jewish) Yemeni silver filigree, is her grandfather’s. The head scarf with Ethiopian batik and tassels was embroidered by her grandmother. This Borderland image represents permeable borders of the past, with the silver filigree done by the Jews of Yemen. It is a blending of countries, cultures and religions.

Why Flux? In this series, Ali directs our attention to the interface of colonialism and the preservation of heritage during these periods of different periods of change. The title “FLUX” derives from “the textile as a document in which politics, economics and histories collide” and their fluidity over time. These FLUX images originate in West Africa with each frame hand-upholstered with wax print sourced from Côte d'Ivoire. In FLUX, visually, there seem to be two broad styles of fabric pattern. The first, as in “Avian Blush,” the figure wrapped in fabric is clearly set apart from a background which is complementary. The lilac colored fabric is finally textured with a stylized bird image positioned in front of a green leaf covered fabric. Some of the images are paired by reversing how the fabrics in the image are used by reversing what is worn, and which is the background. This is the case with “Sojourner Flex,” where there are similar fabric patterns to “Avian Blush,” with the green leaf fabric worn, and the lilac bird image fabric in the background. The fabric wrapped on the frames is also changed in a similar fashion. Alternatively, in other FLUX images, the figure is camouflaged against the background of the same fabric they are wearing. Today, since the wax print process was appropriated by others, one has to now question whether it is authentic from its original source in Java, in Cote d’Ivoire, or is it Indian, Chinese, Dutch, or from somewhere else in Africa. As Ali explains, “In the mid 19th century, the Dutch would engage new technologies to mass-produce wax fabrics to sell to the Javanese market. The look of the batik would be seemingly similar, ultimately different in that it was not as refined as the labor-intensive handcrafted textiles made by batik masters in Java.” This spread of fabric is evidence of a dilution by colonialism of culture as these materials are transported around the globe.

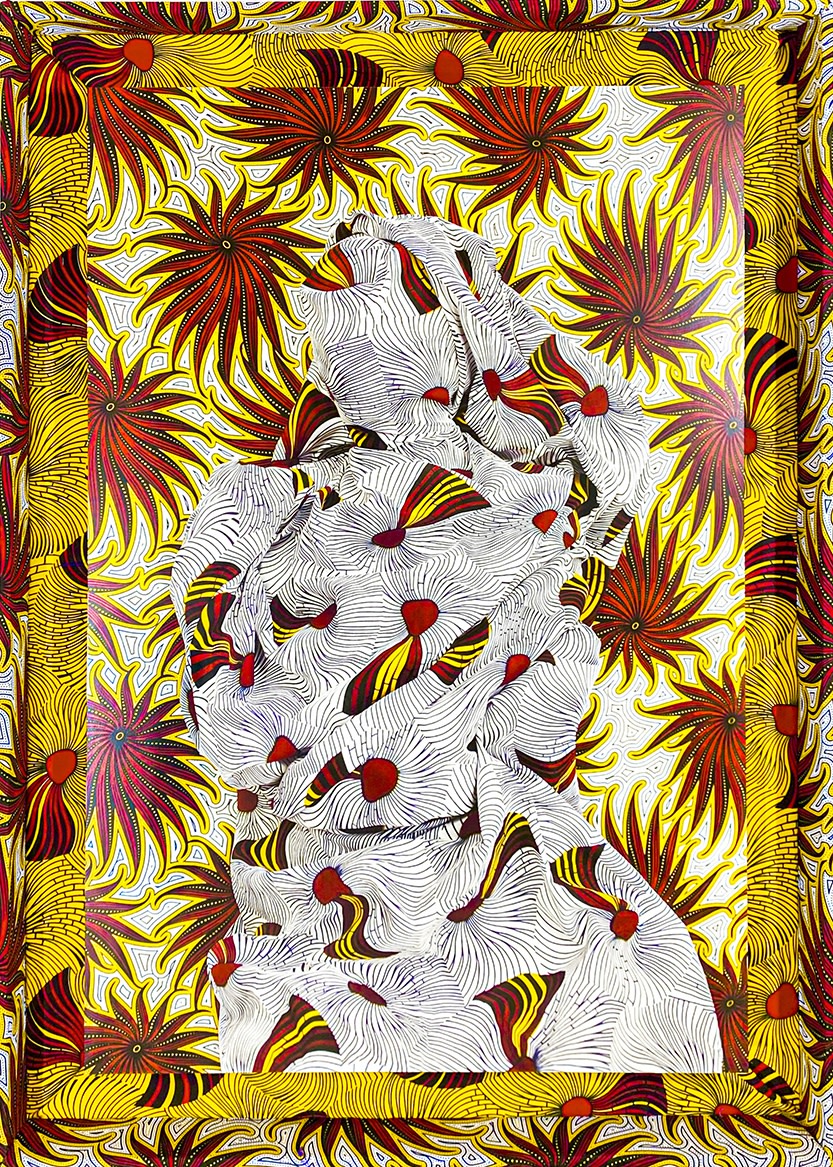

©Alia Ali, Cosmic Vibrations, MIGRATION Series, 2021, pigment print with UV laminate mounted on aluminum dibond in wooden frame upholstered in, Dutch wax print sourced from Senegal, 49 in x 35 in x 3 in // 124.5 cm x 89 cm x 7.5 cm (framed), Edition of 5 + 1 EP + 1 AP

The Migration series of works that are ALi’s expression for the movement of people forced to move across borders. The image title “Cosmic Vibrations” is inspired by the Sun Ra and June Tyson lyrics to “Enlightenment.” This image, as other images within Migration, are explosive in pattern and color. Sun Ra looks at Afro-Futurism that imagines different futures for the African diaspora through technology, fantasy and a science fiction minded approach. This expression of Afro-Futurism also relates to Ali’s own thoughts and practice about Yemeni Futurism. Both movements imagine what a future might be if the present could be revisited and changed. In “Cosmic Vibrations” we see a figure engulfed in a tightly held fabric of black lines traversing a desert-like expanse of a white base with red/yellow shuttlecock-like objects patterned across it. The figure appears in a defiant stance with an apparent confidence against a dramatic pattern of red floral plant-like imagery against black lines crossing over a yellow base. We can imagine a sense of movement as if we too are in migration. What Ali also does with these Migration works is to provoke our imagination of what sort of place and environment these figures exist? She comments that a futurism movement imagines “reorienting their audiences to expansive thinking beyond this world, fraught with trauma of war, colonization, incarceration, slavery, apartheid and genocide.” Where BORDERLAND speaks to us about boundaries, and FLUX focuses a viewer on the cultural appropriation of colonialism, MIGRATION takes the audience one more step in understanding the challenges for people who willingly or unwillingly move across borders.

©Alia Ali, Left: Jan, FLOW Series, 2021; Right: Jin, FLOW Series, 2021, pigment print with UV laminate mounted on aluminum dibond in wooden frame upholstered with a blend of cotton and silk ikat sourced from Uzbekistan, 55 in x 27 x 3 in // 140 x 68.5 x 7.5 cm (framed), Edition of 5 + 1 EP + 1 AP

Why Flow? The FLOW series is based on Ikat fabrics, very recognizable, particularly in fashion, that originate in Uzbekistan. The dramatic fabrics hold a story, as Ali describes in her artist statement, that as areas where these fabrics are produced are colonized or dispersed, there is a threatening dilution of culture, tradition and heritage. Two images in the exhibition are “Jin” and “Jan”, meaning “spirit” and “human’, respectively. “Made of Silk, Cotton or blend, Ikat is created using a resist dye process similar to that of batik like wax print. In certain instances, specific colors and dyes used in Ikat weavings are made in particular communities.” The Ikat fabrics can now be found in many countries outside of Uzbekistan including India, Indonesia [known as Endek], Japan, Central and South East Asia, Argentina, Guatemala, Bolivia, Mexico, Vietnam and Yemen. In some of the images, the third eye, as a concept, symbolizes higher consciousness, enlightenment and precognition or future vision. Ali uses a different body perspective. The frames are longer and narrower, allowing the viewer to enjoy a full look at the rich patterns in these fabrics that are distinctly different from BORDERLAND, FLUX, INDIGO, or LOVE. In a subtle way, Ali uses her artistic skills to visually convey, with fabrics from different parts of the world, in this case, Uzbekistan, a new lesson that again takes another step in expanding a conversation about what people, in areas controlled by others, or people in migration face.

©Alia Ali, Chevron, INDIGO Series, 2019, pigment print with UV laminate mounted on aluminum dibond in white wooden, float frame, 33 in x 33 in // 84 cm x 82 cm, Edition of 5 + 1 EP + 1 AP

Why Indigo? The cotton based fabrics of INDIGO are more universal than BORDERLAND, FLUX, MIGRATION, or FLOW. It was found and used in many parts of the world, so unlike BORDERLAND, FLOW, and FLUX, it is borderless. The word INDIGO derives from the latin name Indian, as the dye was originally exported out of India, and later Guatemala and the West Indies. In Alia Alia’s series, INDIGO, the hue itself stands in as a reference for the migrant experience of disorientation and reorientation. For Ali, it is the sense “… we all share the sky, and our bodies are made up of 80% water, the color blue connects us to the earth, while also sustaining all life forms including plants and animals.” For Ali the color blue unites us physically and cosmically. Indigo is not only found in Japan, India, Java, the indigenous communities in the SAPA region of Vietnam/China/ Laos and the indigenous communities of Mexico, Yemen and the Uzbek Jewish community, but also now globally.

©Alia Ali, أصل (asl) 2 , حب (ḥub) // LOVE Series, 2021, fine art UV flatbed print on aluminum dibond with aluminum subframe, individual works - 42 in x 28 in individual // 107 cm x 72 cm, full set - 42 in x 153 in // 107 cm x 388 cm, Edition of 6 + 1AP + 1 EP

Why, حب (ḥub) // LOVE (2021)? Unlike the other fabric-based works by Ali, the LOVE fabric is created by Ali. She made a wood block of the word حب // LOVE in Arabic that is used to create the fabric used in these images. Words are important to Ali, but she embraces the visual. In this series, Ali uses visual expression for how words can be expressive, yet misunderstood. Preserving and respecting tradition, one’s “roots" so to speak, is so very important to Ali. She is concerned how events collide causing an extinction where people have “lost their native tongue leading to the erasure of an entire generation’s stories, heritage, and connection to their roots.” In her work, we visualize ancient ways crashing upon current events that define (or re-define) our future path. It is in these works that Ali puts before the sensitive use of translated languages. Unlike the other fabric-based works by Ali, the حب (ḥub) // LOVE fabric is created by Ali. It is in these works that Ali puts before us the sensitive use of translated languages. The LOVE work is divided into 9 groups of 5 images each using a variety of colors. Each of the nine (9) groups is defined by the expressive pose and gesture of a person, with dramatically different wraps and folds of fabric around the body and head. The nine different poses are also titled differently. Each title in LOVE has one of the adjectives, describing an aspect of LOVE preceding it. The images shown is أصل (asl) 2. أصل (asl) translates as: origin, descent, parent, root, ancestry, or principle. How a word translates changes the meaning and context, and how the viewer may imagine the image.

This work illustrates how language used, out of context, can lead to misunderstanding. Each of these Arabic words have multiple meanings. How each word is used changes our context for viewing the image. The title of images in Ali’s work is purposeful and tightly integrated into her lesson for us, the viewers. It forces us to think and consider the meaning of a work and its translation. In FLUX, FLOW, and BORDERLAND, the title conveys a hint of the story, as each pattern is very dynamically different from the next, while each LOVE image fabric is the same in design. The LOVE series images differ in pose and color, but the fabric is a constant. The figures visually position us to be mindful of what words mean, properly translated. Words can be misused, twisted and the context translated incorrectly. It is the old expression “what I said isn’t what you thought I meant” or you “twisted what I meant to say.” How words are used are often taken out of context. This concern is front and center in Ali’s “Love” series. This is up to the viewer, and unanswered by Ali. The non-verbal visual translation spoken to us through these images is what we see and study within our own imagination and impression. It is here that she brings full attention to the language of and within fabrics.

Ali’s BORDERLAND, FLUX, MIGRATION, FLOW, INDIGO, and LOVE series open an expressive use of one art form within another. Her works are a beautiful combination of photography, textile and the hand craftsmanship of the frames. “Textile is significant as it is something that we are born into, we sleep in it, we eat on it, we define ourselves by it, we shield ourselves with it and, eventually, we die in it. … The use of textile is significant as it’s sourced from the earth to be woven into something that protects, defines, unifies, and divides us–– it becomes a point of departure from where we all begin.” It is rare to have an artist with a body of work that literally expands the globe. In “Cartographies of Pattern,” Ali’s work invites the viewer to be a time traveler, anthropologist, sociologist, and simultaneously have our eyes widely opened. These fabrics take us around the globe in a fashion without borders. Within the appreciation of the beauty of the textiles in each of these creations, we share an experience with other people, regardless of origin. The works of Alia Ali, without our knowing it, have placed us in a space that is borderless with appreciation of what is also unique and special.