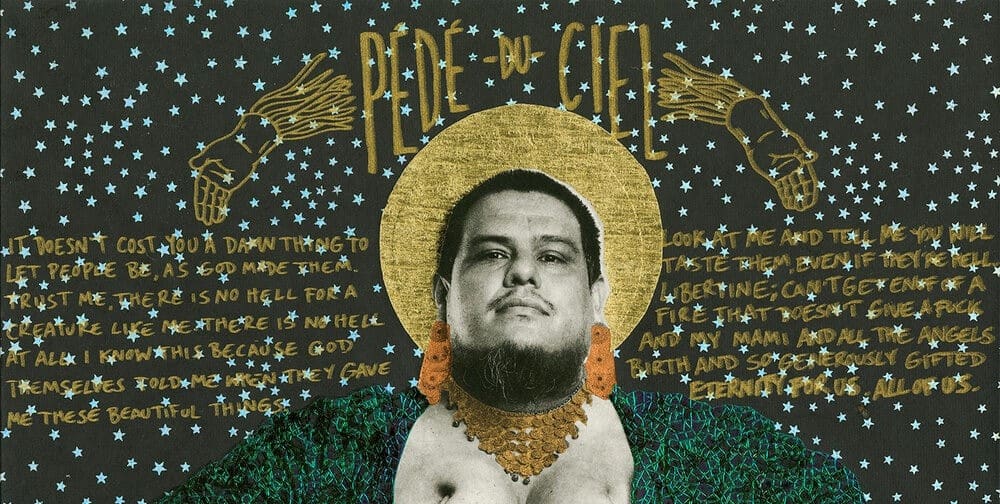

Gabriel García Román, Dorian, 2019

The Body as Memory investigates the ways in which the body interacts with the environment around it—the cultures it is born into, how it is viewed, how it views itself within that context, and how it imagines itself. It seeks to recognize the queer body as a historical site of injustice, yet, through acceptance, present the body as a site of exultation (and exaltation) instead.

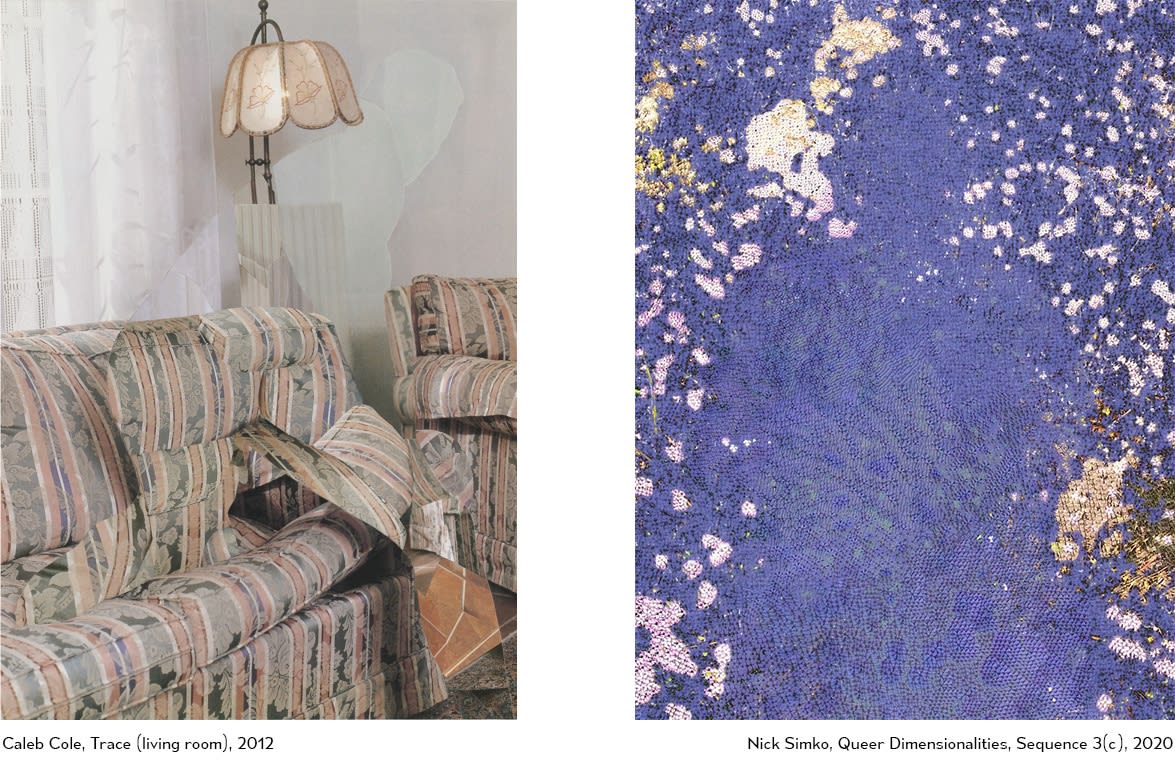

Caleb Cole, Nick Simko, and Gabriel García Román each tackle concepts of identity and queerness through the lens of their own unique experiences. Having grown up with a passion for thrifting and second-hand objects, Cole’s work reflects a deep desire to connect with histories lost to time, stories that are just as personal as they are collective. Simko’s interest in intersections of technology and authenticity tie into this discussion of recorded histories, questioning what is missing from the narrative and how much of that which remains is artifice. Simko also seeks to test the limits of photography’s ability to express his own queerness in textural, spatial, and atmospheric ways. García Román’s background in the Roman Catholic church inspired him to co-opt the aesthetics of traditional religious iconography to elevate individuals who are underrepresented and often pushed to the margins of Western communities.

In the works brought together for this show, the visual form of the body serves as a vessel, telling a story, or only parts of a story, or even leaving the story entirely untold, leaving the viewer to question what is missing, what has been lost. Memory is a powerful force, and queer and minority histories are systematically erased by those who control the larger narrative. They say history is written by the victors, when, in fact, it is written by the oppressors. The works in The Body as Memory touch on different points in this process: the active twisting of history through omission; the passively violent erasure of an entire queer generation, along with their stories, during the AIDS crisis; the modern experience of living as a queer individual in a world not made for us; and finally, a look towards a brighter future which turns traditional visual language on its head.

When I think about queerness — my own experience, how I interact with others in my community, how queerness is discussed in mainstream culture — I almost always come to think about the body. The body, that pesky thing — it binds us to the material plane; it is the lens through which the rest of the world views you, judges you, often defines you. For many queer and gender nonconforming people, it can be a burden, sometimes a betrayal. The body is the vessel which carries the true self, the self that exists in thought and spirit.

There are many reasons why people feel disconnected from their bodies. In a world where images and information and advertisements are constantly assailing us, we are told there is a right way to look, a standard of beauty to uphold that is rooted in misogyny, heteronormativity, and Eurocentrism. Bodies existing visibly on the margins of those ideals are subject to prejudices and harmful assumptions in many aspects of their lives — at school and in the workplace, in housing situations, in grocery stores, in the doctor’s office, in every imaginable place. Sometimes, a body can feel like a cage that you cannot escape. Even in the face of all this, it can still become a site of absolution.

My own journey with queerness has been unique to me, and I cannot presume to speak for the vastly and beautifully varied experiences of all others in my community. It is an understanding which has been informed by the culture I was raised in, the language I learned to translate experience through, the friends who have shared the path of self-discovery with me, and those who have been loud and unabashed about who they are and how they exist in the world. Language is very powerful in determining how we shape our thoughts. I, like many others of my generation, use the label queer as a means of encouraging solidarity, to avoid the pigeonholing of individual identities, and as a term that allows for fluidity of identity as we grow and learn. The beauty of queerness is truly in community, in finding a space to be true to oneself. Queer author and activist bell hooks said it best:

"queer not as being about who you're having sex with (that can be a dimension of it); but queer as being about the self that is at odds with everything around it and has to invent and create and find a place to speak and to thrive and to live."

Even gender nonconformity is not safe from the incessant categorizing impulse of Western society. As the concept of nonbinary, agender, genderfluid, genderqueer, etc. identities become more widely discussed in mainstream Western culture, they have become associated with a specific look, a body. Thin, white, and androgynous is the new expectation, regardless of the fact that gender identities outside of the binary have existed(and still exist) prominently in many cultures, especially non-white ones, throughout history. To explore only two such examples out of countless others: Two-Spirit is an umbrella term meant to unify the various gender identities and expressions of Indigenous Americans; it is a modern term coined in Winnipeg in 1990 from an Ojibwe translation, and it does not perfectly describe the varied forms of gender expression across different Indigenous languages and cultures. Within Hinduism, hijra and kinnar are just two words used to refer to gender nonconforming identities, among many other nuanced terms. Both Hijra and Two-Spirit individuals hold historically important roles in the religious practice and mythologies of their respective cultures. The complexity of these nuanced identities cannot be simplified into a 1:1 translation to the Western concept of nonbinary gender. Although the Western world may consider itself to be progressive in today’s context, it is important to remember that the reason many queer people face discrimination across the globe is as a direct result of European and US colonization. Colonizing nations leveraged Christian principles through enforced laws and policies intended to destroy indigenous ways of life, and the effects of those policies are still being felt today as new forms of cultural colonization persist.

Each artist in this show explores queer realities: historical, current, and speculative. Understanding where we have come from is essential to imagining the endless possibilities of where we are going. The queer struggle for liberation is not a new one, and anyone reducing it to any one generation or framing it as some newfangled concept is attempting to discredit its legitimacy and importance. When it comes to approaching queerness as an outsider, the vast diversity of our community, language, and experience can be overwhelming. I ask that you do not let it strike you as daunting — rather, let it strike you as an opportunity to listen and learn. We are all translating new information through the lens of our individual cultural biases — realizing that limitation is key to deconstructing it.

Nick Simko, The Power to Choose, 2015

Related artist

Share

- Tumblr

Add a comment

-

Recent posts

- JP Terlizzi's Creatures of Curiosity January 9, 2024

- Composite Realities: The Art in Architecture October 11, 2023

- What is Contemporary Photography? (Revisited) September 23, 2023

- Temporality and the Landscape Photograph February 25, 2023

- Restless Symmetries: The Work of Barbara Strigel and Kelda Van Patten June 29, 2022