Amanda Marchand, a Canadian photographer living in Brooklyn, New York, is an artist using a camera-less photographic process to create lumen prints. Her work is intimately tied to and dependent on nature to create images on a variety of light sensitive photographic papers. A Lumen, or sunprint, is created from the interaction of sunlight, object, and paper to create an unpredictable but colorful visual of shapes from objects placed on the paper. Marchand then scans the temporal lumen images as an act of preservation of the revealed ephemeral colors. Once scanned, a print is then made, cut exactly along the lines of the original pieces of paper, and arranged for an abstract expression of some part of our natural environment. The artistry in the exhibition “Lumen Notebook” arises from both the process and creative expression.

An original lumen print is a unique work created from placing objects on a light sensitive silver gelatin paper, and exposing it to light. It can be referred to as a “solargram” or, by technique, a “photogram.” A photogram is the process where objects placed on paper (or film) and then exposed to light leave a “shadow’ outline of what was placed on the paper. An actual camera, as we know it, is not used, hence the technique is also referred to as “camera-less" photography. Only paper, light, and shadow is needed. If the object lies on the paper flat, there is a sharper line and definition of the object. If the object is rounded or not flush to the light sensitive paper, then the image outline is softer, fuzzier. The more three dimensional an object, the more the shadow of the image created hints at that object’s existence with soft shadow. Each original lumen collage in the collection is, itself, a unique print as Marchand hand cuts the papers into multi-paneled collages. Marchand’s artistry is in mastering this technique to create these beautiful images.

Often, older black & white silver gelatin (light sensitive) papers are used. The trigger for the paper to turn from white to some color is from exposure to either natural light or an alternative artificial light source. UV Light can be used, but Marchand uses sunlight for her exposures. How long the paper is exposed will determine the intensity and shade of color revealed. Exposures can take from seconds to hours or even longer, and the paper, while meant to create a black & white image when used in a traditional darkroom, will deliver a range of colors unique to that paper, manufacturer, and age.The color may also be affected by the humidity, clouds, and temperature. What happens to each sheet of paper evolves as a unique measure of time, place, and environment.

“Whooping Crane” (Adorama RC Pearl), from the series, “The World is Astonishing With You in it: A 21st Century Field Guide to the Birds, Ferns and Wildflowers,” by ©Amanda Marchand

However, the Lumen printmaking process presents a “Catch-22.” The photographic paper’s color continues to change the longer it interacts with light, unless chemically “fixed,” meaning immersed in a “hypo” chemical solution. The chemical “fix” process destroys the varied colors, altering their color. Unfixed, the paper will continue to change color as light darkens the paper further. Marchand deals with this conundrum by scanning the lumen, creating a digital image of the paper’s color and preserving the image at a point in time. “Chemical fix dramatically alters lumen color. Because of this, I have been using a scanner to “preserve” lumen color, where the scanner light participates in making the final image. I like how this tool expands the conversation I’m interested in about time, merging early photographic processes with new technology.” The exposure to light thus becomes a record and mark of time. While a reasonable solution, the light from the scanner will also change the color of the paper. But this does not bother Marchand: “I’m excited by the fact that the scanner is part of the making of the image, is in fact necessary for the reading of the lumen color, that it changes the original even as it records it. This seems unique to photography and fascinates me. I don’t feel there is any loss here, only a more complex understanding of how images can be made and what photography is, in fact. The image exists as a conversation between analog and digital.”

There is a history of well-known photographers that have used the photogram process. The earliest discussion of experimentation to capture an image occurs in the early 1700s with work by a German scientist, Johann Heinrich Schultz, experimenting with silver nitrates. As the story goes, he noticed the effect of sunlight on the chemicals in a jar when a stencil that was wrapped around the jar began to form letters in the chemical material. There was no way to permanently preserve what was created, but his experiments helped the march toward capturing images of nature. In the 1790s, Thomas Wedgwood sought to create images on paper and leather by coating these materials with a light sensitive solution. Again, there was no existing method to arrest exposure to light, to “fix” or make permanent the image. It was not until the early 1800s that the work, close in time to each discovery, of Joseph Nicéphore Niépce (who created the earliest known surviving photograph, held at the Harry Ransom Center, at the University of Texas), Henry Fox Talbot (who invented the calotype), and Louis Jacques Mandé Daguerre (creator of the daguerreotype) found a way that an image could be captured and permanently preserved on a paper or metal surface.

Lumen prints first appeared in the earliest days of photography in the 1830’s through Henry Fox Talbot’s “photogenic drawings.” Lumen prints are part of the history of photograms. That photogram history is relevant to the exploration of photographic processes and our understanding of lumen print image creation. In the 1840s, the cyanotype process (a process that did not use silver nitrate, but an iron (ferric) salt) was discovered by Sir John Frederich William Hershel. The cyanotype, another form of photogram, with it’s tell-tale blue color (versus black, grays, and whites of the silver-nitrate based images) was brought to public attention by the work of Anna Atkins in the early 1800’s. Atkins may also have created the first photography illustrated book using cyanotype images of plants and seaweed in England. Cyanotypes then became another popular form of “photogram.” For a number of years the use of photograms lay somewhat fallow until the 1920’s when artists like Man Ray (“Rayographs”), Laszlo Maholy-Nagy, Christian Shad (“Shadographs”) and others began to use the photogram technique as a form of artistic expression. With the rise of Dada and other art movements of the 1920s, artists like Man Ray and Schad used all manner of objects like springs, pipes, combs, nuts and bolts in the experimentation and abstraction of images. More contemporary photographers using these methods are Adam Fuss, Floris M. Neususs, Susan Derges. and Meghann Riepenhoff. Derges and Riepenhoff used the outdoors as a darkroom immersing paper in streams, oceans or placed in other natural settings to imprint on paper the image of the flow of water, snow, rain, plants and trees.

“Drawer 1” by ©Amanda Marchand, from the series “All is Not Lost”

It is also interesting to note that based on research by conservators at MoMA, Man Ray published a small album of 12 of his Rayographs, “Champs Délicieux,” in 1922 by photographing the Rayographs and reprinting the image on photographic paper that was then tipped into the album. Marchand’s procedure of scanning lumen prints as part of an alternative photographic process, while different from Man Ray, has this precedent.

For Marchand, these photographs are the result of presence, inspired by sitting in the outdoors, that she wants to share with the viewer. The lumen process requires Marchand to slow down, think, reflect and meditate. She started making lumens with people sitting in a “circle of meditation,” seated on unexposed paper, outdoors, that left an impression of their bodies on the paper as they co-existed for approximately half an hour together. From that experience, Marchand started looking for other photographic papers with which to create lumen prints. She realized that a different color palette was revealed with each box and type of paper, whether matte, gloss, or semi-gloss. The process of creating these lumen prints is meditation for her. It takes time to expose each piece of paper, and the exposures permit a tuning in to the natural world that surrounds her as she makes the work. The making of the photograph requires that she slow down, count time, and wait.

Marchand started out as a writer, before fully embracing photography. “This project often feels to me like a writing project, in that each unique lumen piece begins with text. Over the past 5 years, I have been making collages inspired by the title of books, which I repurpose as my image titles. In traditional photography, images are made and then titled second (or not at all). The work in Lumen Notebook, begins with language. The images are not secondary, but come second as a response to words. As someone who is always asking the question, ‘What is a photograph?’ this feels interesting to me.” The use of books placed upon the paper comes from her love of literature and art books, regarding a book as a medium of communication and memory with an aura of its own. “The lumens that index specific books are often displayed as multiples, stacked together like the piles of books in my studio and at my bedside. Most are books on nature, some on art and photography.” The titles of the books become part of the inspiration for her abstractions. “The images reference pictorial components of the landscape, horizon lines and vertical markers, the movement of sun across sky... Many of the books I use are dear to me.” She also gave herself a set of rules for creating images. She states, about the self-imposed “vocabulary" for the project, “My rule was that I could make only one mark per piece of paper with a book. I am using, usually, 4 pieces of paper for one book, sometimes 2 pieces or 1 piece of paper per book. This limitation directed the visual language of the project.” Other series of works within the “Lumen Notebook” exhibition are arranged and collaged images that relate to how the artwork was created or assembled, but with variations on this motivation: “Timelines,” “No Title Required,” “All is not Lost,” and “Stacks.”

“A Friend is a Soul in 5 Bodies” by ©Amanda Marchand, from the series “No Title Required”

“The World is Astonishing with You in it: A 21st Century Field Guide to the Birds, Ferns and Wildflowers,” is a collection of collaged lumen images that references disappearing species. She comments “This work employs three field guides – field guides to North American birds, ferns, and wildflowers that belonged to my late mother. I mark/expose the photographic paper, making one mark per quadrant or half, with an edge of the respective book. Every paper type and brand turns a different latent color - what I think of as the paper’s own ‘color alphabet’. I have experimented with at least 100 different papers,both current and expired. With abstract bird shapes (beaks, wings, eggs etc.), brute fern shapes, and flower shapes, each lumen photogram in this series references an endangered bird, fern, or flower.”

“Horizon - Paper Negative” (Ilford MG FB 1P) by ©Amanda Marchand, from “Stacks”

Amanda’s work is a visual correspondence with nature, and the visual creation, in both form and color, eases our inner selves. The current work follows earlier works by Marchand like “True North.” In an interview with Kyra Schmidt of “Aint-Bad” (03/13/2019), Marchand stated “‘True North,’ as the title suggests, is about re-directing to one’s own center. It was made very much with the awareness of deep-space time, set against the barrage of information, advertising, texting, email, deadlines, rushing and exhaustion that defines most of today. … I think I also felt that, the way the world is going, someone has to bear witness to it, before this is all gone, someone needs to just actively observe, love and appreciate this.”

To create the lumen prints, Amanda finds creative ways to expose her papers to the sunlight. With “All is Not Lost,” Marchand shared that “the title was framed around the drawers set in a wall at Hewnoaks Artist Residency. For the installation, I did not ‘fix’ or scan the lumens before exhibiting them. I placed them in the drawers set in the wall, and the audience was invited to open the drawers, further exposing the images, and in fact controlling whether all would be lost or not. The title referred to the experience of enjoying what is fleeting, as well as the fact that old furniture, drawers, have a history retaining some aura of the past, as do books. The images are made with books found in the Hewnoaks’ studio library, on nature, ecology and the landscape. In order to ‘fix’ lumen images, in other projects, I employ a scanner. The use of this tool lends to a larger conversation about time I’m interested in, wedding earliest photographic process (lumen printing) with new technologies (scanner).” Marchand then assembles the various papers then into a wonderful arrangement where the book floats from segment to segment in a contained abstraction.

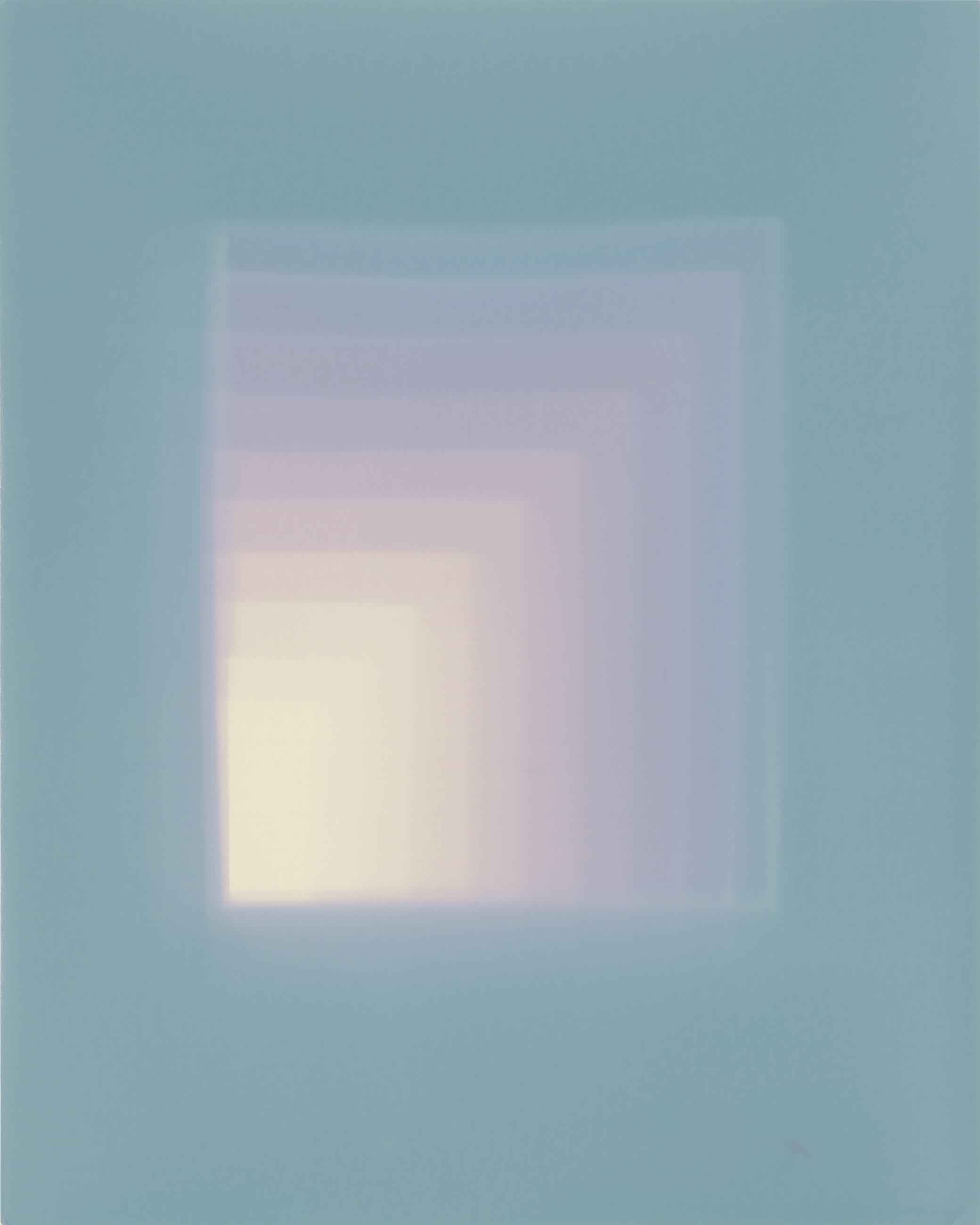

“Event Horizon (BlueGreen)” (Ilford BLMOP Glossy), by ©Amanda Marchand, from the series “Timelines”

“No Title Required” was created during her time at the Datz Museum Artist Residency in South Korea. The title came from a poem by this name in Wilslawa Szymborska’s book, “View With A Grain of Sand." This was one of the books selected by the Museum and Press Director, Sangyon Joo, for her photogram. Marchand describes the process: “At Datz Museum of Art, I asked the all-women-team there who run the residency, museum and press, to select books by, or featuring, their heroines. I made photograms with the old darkroom papers they had on hand and the books they brought me. Each image was titled with the book (or one of the books) that made the photogram. The 10 images in this series were made with the light of the sun in July on the residency grounds, a bucolic mountainside.”

The title for "A Friend is A Soul in 5 Bodies" came from the manager of Datz Press, Juyoung Jung, who had selected a type of journal she had made with 4 of her best friends' photos and letters inside to use for the photogram. Her journal was titled that way. She spoke of these four friends as being her “heroines." The words “A Friend is a Soul in Five Bodies” is also a reference to Hindu writing and philosophy about our souls. The expression “One of the ways of understanding the soul is to understand what it isn’t” can be found on the Kauai’s Hindu Monastery website. The collection of books in this image, as hinted at by the title, may be a request by the artist for the viewer to reflect upon this.

For “Stacks,” the image “Horizon” is a diptych with one print placed on top of another. Marchand commented on her inspiration for this work: “I had started making these and was thinking of calling them ‘Stacks’ just a few weeks before I went to see the Donald Judd show at the NY MoMA. These were a 2-D representation of the 3-D real life stacks of books on the floor in my studio and home. I was excited to see that show and really identified with Judd's sequential works and color shifts and playful counting and layering etc. After seeing Judd's "Stacks" I decided that it was really the perfect title to use. … I have two pieces with horizon names from ‘Stacks.’ The first is ‘Horizon Magazine,’ where I used a magazine called ‘Horizon’ to make the photogram. The second is called - and you selected for the show - ‘Horizon (Paper Negative).’ I used a personal journal to make the darker half, then used that as the paper negative to make the other lighter half. I had been drawn to the horizon line for several decades when I photographed the landscape. I like how it is something seen with the eye and camera but is a kind of optical illusion.”

Her newest work, the “Event Horizons” is part of her series “Timelines.” Rather than have a static placement of a book on the paper, boxes and envelopes of photo paper are shuffled across the lumen print paper at defined times, creating not only a sense of depth as the exposure to sunlight varies like a darkroom test strip, but giving the image a very powerful sense of movement from the passage of time. Marchand comments “The ‘Timelines’ and ‘Event Horizons’ have multiple marks per paper. These pieces employ the same method of moving a photo box or photo envelope across the paper to create a gradient. These are not planned pieces, but actual test-strips, gauging color parameters and density range of different papers. They reference darkroom test-strips, the slow counting of time, quantum physics, and color spectrums in nature and photography.”

In addition to her photographic works, Marchand’s practice includes making and publishing photo books. Among others, she recently published “The World is Astonishing with You in it: A 21st Century Field Guide to the Birds, Ferns and Wildflowers.” Two earlier monographs "Nothing Will Ever be the Same Again" (2019), and “Night Garden” (2015) were published by Datz Press.

The resurrection of the photogram process by Amanda Marchand brings a new dimension in its use of color and in marking the passage of time. In addition, by cutting and arranging the paper to create abstractions of horizons, birds, plants and other features in nature, her abstractions yield yet another special feature of the “Lumen Notebook” exhibition. One is not only enticed by the variety of the arrangements, but transfixed by imagination and visual stimulation to ponder what each work represents. Marchand takes the viewer on a walk through an untouched world. We can mark the passage of time with “Event Horizon” images or we can picture, in our mind’s-eye, the actual whooping crane in her abstraction by that name. We look at the arrangements made by the shadow of books on nature and, again, contemplate what we might see and read in the text as if we held it in our own hands. True to Marchand’s inspiration, we as the viewer slow down, relax and reflect as if we, too, are walking that same path with her, or sitting in a garden.