David Reinfeld’s Composite Realities embraces the art in architecture and the surrounding environment. Throughout photographic history, the capturing of buildings, streets, and cityscapes has been a ubiquitous fodder for artists and photographers. Reinfeld’s work incorporates abstractions of fragmented buildings along with pieces of detritus and layered torn plastered signs. Having received his MFA from the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD), he is a street photographer with an informed bias. How he “sees” has been influenced by New Bauhaus artists infused by earlier industrial art movements also embracing art, science, and design. It is with this background that we can begin to look at David Reinfeld’s Composite Realities.

The depiction of buildings, in part or as a whole, has always been closely entwined with photography. The very earliest photograph known, Untitled (Point de Vue, 1827), a Heliograph by Joseph Nicéphore Niépce of France, was taken from a room looking out over nearby buildings and rooftops. Architectural compositions were easy subjects for the early low technology cameras since a building would not move or shake. French Photographer, Eugène Atget (1857-1927) literally walked the streets of Paris to document and visually preserve buildings and parts of the city that were systematically being replaced. As time progressed, photographers became more adventuresome, climbing up buildings under construction to capture dramatic views or aerial backdrops. Artists appreciated not only the whole of a building, but also each its parts, celebrating the artistry of a window, door, wall, and roof line.

In Reinfeld’s visual exploration, his compositions leverage shape, structure, leading lines, angles, and pattern accentuated by light and shadow. While at RISD, his “eye” was shaped by the Constructivism and Bauhaus art movements where art and architecture found common ground. Constructivism was abstract, used space and shape to reflect modern industrial society and urban space. The Bauhaus movement embraced this Constructivist interest in industrial materials, geometric forms like the triangle, square, and circle and asymmetry as a rejection of earlier decorative and naturalistic movements. Abstractionist movements then followed. Reinfeld worked his feelings for the city into constructed and unconstructed image creation. His photography spans the literal, interpretive, and abstract unified by a focus on his life within New York City.

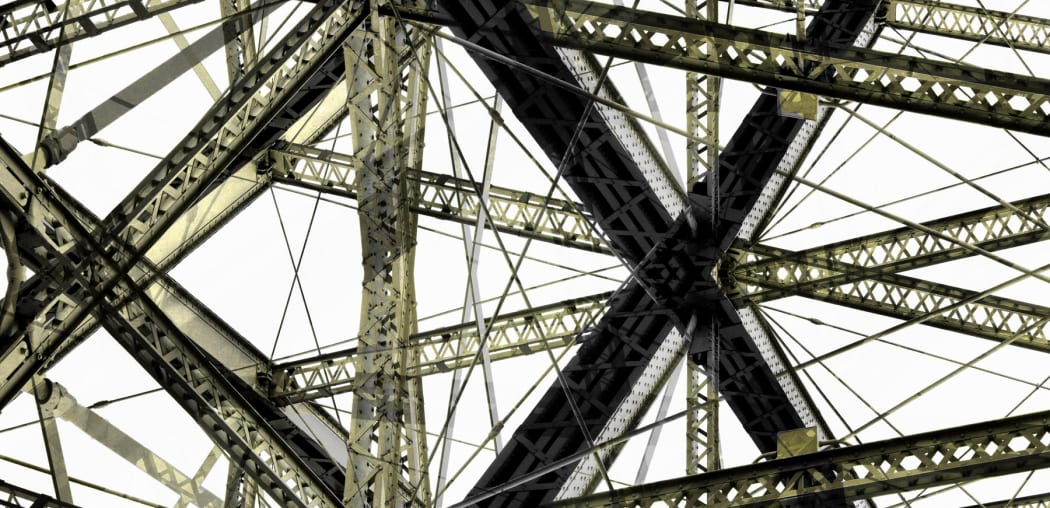

Reinfeld’s visual world is one of pattern and structure. He comments: “Structure stands against gravity. So much of how we live our lives is defined by our relationship to gravity.” There is a sense of Constructivism in his images, seen in his use of collage and sharp angles with a focus on girders and window segments, which echoes non-photographic work by El Lissitsky (such as the carefully planned constructed abstraction of Proun 19D, 1921). At the same time in Reinfeld’s work, we can also sense the pull of abstract impressionist influence from artists like Willem de Kooning (see Interchange, 1955). Reinfeld adds: “The world relies upon the structures to hold what is built together. I photograph bridges and buildings, fascinated by every detail of their skeletal structure. What keeps a bridge from flying apart? What keeps a building from collapsing upon its own weight? It is sometimes obvious how girders and beams are welded together to create structure, yet there are times when the structure involved is incomprehensible. These images are composited photographs of structure upon structure, exploring the designs to create a single arrangement, holding itself together […] This underlying elegance of the connections form a perfectly constructed visual world.” Reinfeld’s work visualizes for us the design and movement in our urban environment. Rather than degrade and tear down what constitutes the city landscape, he finds beauty in the component parts that make up the abstractions he has created in his constructed images.

The architecture-based abstractions by Reinfeld in the exhibition Composite Realities are in three separate bodies of work: Reliance (steel girders), Confines (brick painted surfaces) and Schrödinger’s Cat (the glass sides of buildings). In Confines 4 Reinfeld embraces a pleasing blend of color on brick walls. He highlights the visual of a bridge’s iron structure, and the steel skeleton of buildings under construction that can be seen in Reliance 5. In the Schrödinger’s Cat composites, he takes the refractions and reflections of windows in gyrating abstractions. Yet, our eye is contained within the frame. We don’t fall out of the image but are left with a sense of floating about within the triangular and trapezoidal extractions. Reinfeld comments: “I had the privilege of studying with Harry Callahan, Aaron Siskind, Lisette Model, and Minor White when I went to RISD in 1973 for an MFA in Photography. I was an untrained artist, with no formal education. Essentially, I was a New York City street photographer with the idealism of the 60s. Having a scientific education, I was able to learn the technical aspects of photography, along with the social and political nature of the times. At RISD, everything changed. I was exposed to aestheticism for the first time and how the construction of an image was an essential part of expressing myself through the photographic medium. Harry and Aaron were consummate artists with seemingly different approaches. Taken together, they taught me different ways to approach image making. Harry was a realist and romantic, whereas Aaron saw the world abstractly. As Harry would say to Aaron (paraphrased), ‘When I photograph a wall, it’s a wall. But when you photograph a wall, it’s something else.’ I tended to see more abstractly like Aaron, yet think more philosophically like Lisette. Harry introduced to me that the ordinary things we see are the most extraordinary.”

Not all of Reinfeld’s work is constructed or composite imagery. Often, his work is a “straight” capture of what he sees. For certain works, Reinfeld records what he sees, unaltered. “Taken all together, I realized image making was a collaboration of ideas and aesthetics, the subject and the camera. I saw this as magic, and too much control of the process was not helpful for me making images. Put another way, a photograph should be on purpose but not too much on purpose.” This is where the works Unintended Consequences I, II,and III speak directly to the viewer separately and together. Reinfeld comments: “The cities are splattered with posters on building walls. They start out whole, as advertisements. Then they are torn, ripped from marketing, and become the social icons of our culture […] Walls splattered with symbols have become the telling cultural icons in our society. Our world is knocked down and rebuilt every moment, every day. Every tag is a living history.” One of his previous professors at RISD, Siskind, is known for his capture of painted, graffitied and torn remnants on exterior building walls. Siskind reveled in the dramatic chiaroscuro of light and dark cast, as demonstrated in Lima 137 (1975), a black and white image with layers upon layers of paper. It gives the effect as if looking at the side of a canyon wall with rocks jutting out above where decades of erosion have carved out the rock face. Jerome, Arizona 21 (1949), another black and white close-up image, shows a section of wall with layers upon older layers of cracked off white paint, curling up like leaves and petals and peeling off the wall as dried leaves would appear on the ground in fall. The influence of Siskind is evident as a celebration in the visual enjoyment of decay, layers, perspective, and light. Although influenced by Siskind, Reinfeld’s color images are interested in more than pattern. He challenges the viewer to see something more within the image, perhaps an abstracted outline of a person. It is notable that in these works, images of people are not directly included, except partially in Unintended Consequences 2. In other images in the series, their presence is only suggested.

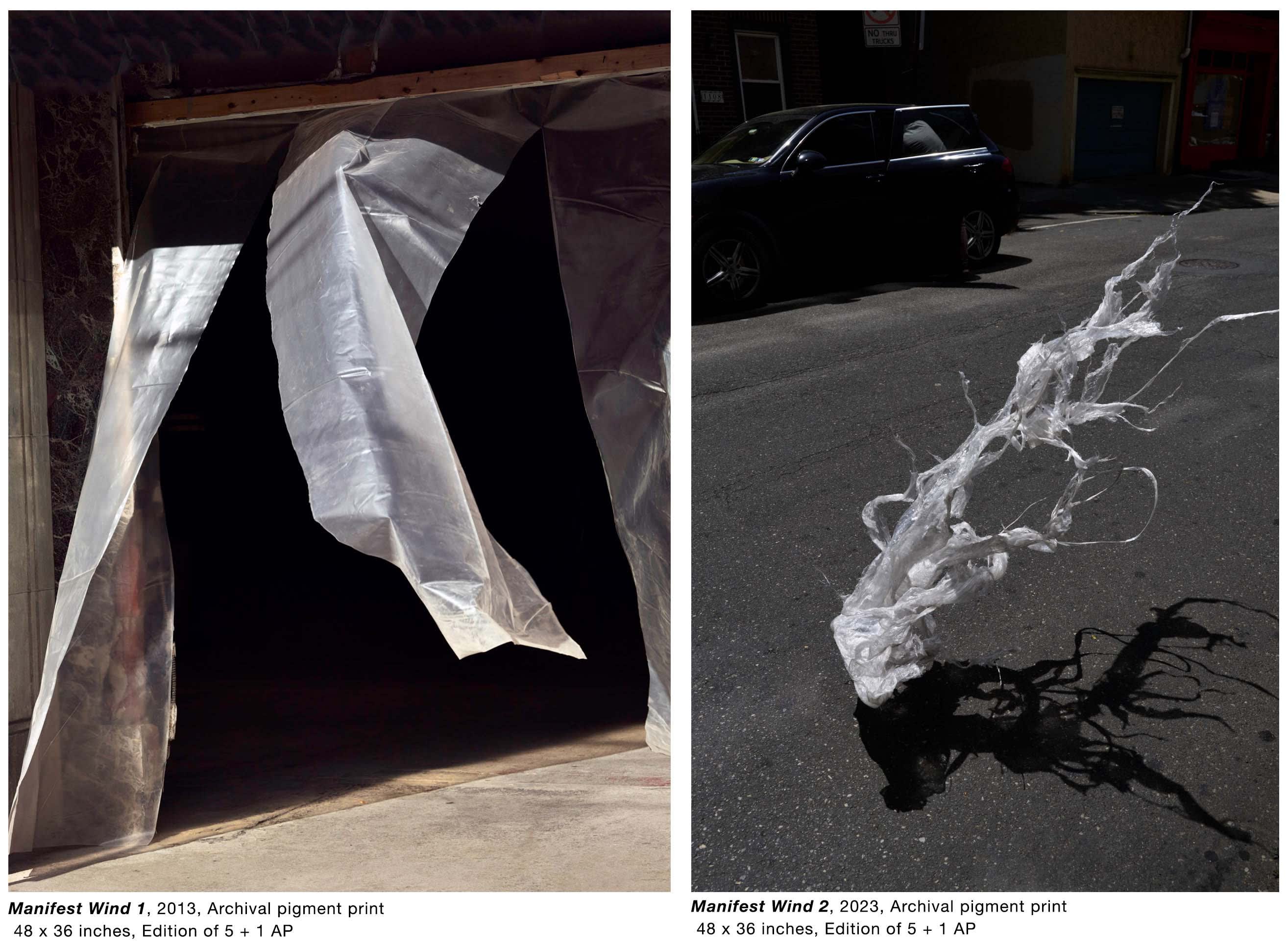

In Manifest Wind, Reinfeld celebrates the unpredictable gestures a breeze creates where it passes by. He explains: “These images show how the invisible elements surrounding our lives unpredictably create new points of reference in both subtle and dramatic ways. For what we cannot control, we provide meaning as a matter of choice. I think the idea for Manifest Wind came to me when I was very young; I remember watching the wind blowing for hours on end, always trying to predict what may happen, and then usually being wrong. The photographs are very much a part of different aesthetic constructs—movement and action, and the philosophical ambiguity of real time. I've always been intrigued by how the things we cannot see can influence the things we do see. When I make these photographs, I look for how the wind brings ordinary shapes to life, simply out of thin air! Somehow this process seems to animate what is not. Manifest Wind is my metaphor for photography as magic, where what we see as hidden in plain sight comes into being like a train coming around the bend.”

In Manifest Wind 1, Reinfeld’s careful eye catches wind blowing through a plastic sheet covering an entryway, while Manifest Wind 2 captures a dynamic, almost sculptural mass of plastic seemingly suspended over the street. These images could remind the viewer of Aaron Siskind’s famous series Pleasures and Terror of Levitation, where divers are caught silhouetted in different positions against a blank, empty sky. What would otherwise be walked past and ignored becomes an invitation into the dark space beyond. We have no idea how long those sheets have hung there, and where the door leads. The wind has caused the plastic barrier to open as if to invite us into the unknown. This is so often how we experience the city, especially a city as old New York, with its many layers of structures almost waiting to be excavated. The image is a reminder that through each portal and behind each wall there is a history of something constructed, destroyed, or suspended in time, the former inhabitants long gone, spaces abandoned and refilled, holding memories lost to time. Manifest Wind 2 is a companion statement to Manifest Wind 1 that speaks to life in a large city like New York. Unlike the plastic sheets hanging with some purpose in Manifest Wind 1, our subject is discarded plastic, floating into the street as a beautiful moment of elegance and at the same time a statement of waste, pollution, and environmental hazard. It is a combination of beauty and threat. The contrast between the two images highlights decay and change—a side-by-side cycle of city life.

In Composite Realities, Reinfeld is an urban documentarian with a twist. As a New Yorker, he finds no shortage of intriguing visual content around him in his daily life: layered scrapes of posters on walls, painted surfaces, windows and mammoth steel fabrications and frames rising from the concrete. His images are both non-constructed and constructed, as he experiments with reflecting the constant change and impermanence of urban life. While his images are not documentary in a traditional sense, they are a celebration of the color and excitement, the chaos, change, and presence of the city at this moment in time. These are the works of one photographer carrying forward prior decades of thought on expression in art, infused with his own contemporary experience, to become these “composite realities.” Not merely visual composites, Reinfeld’s creations are composites of decades of inspirations and influences, the history of photography and the history of the city, folded and shaped into each final image like a record of time and space.